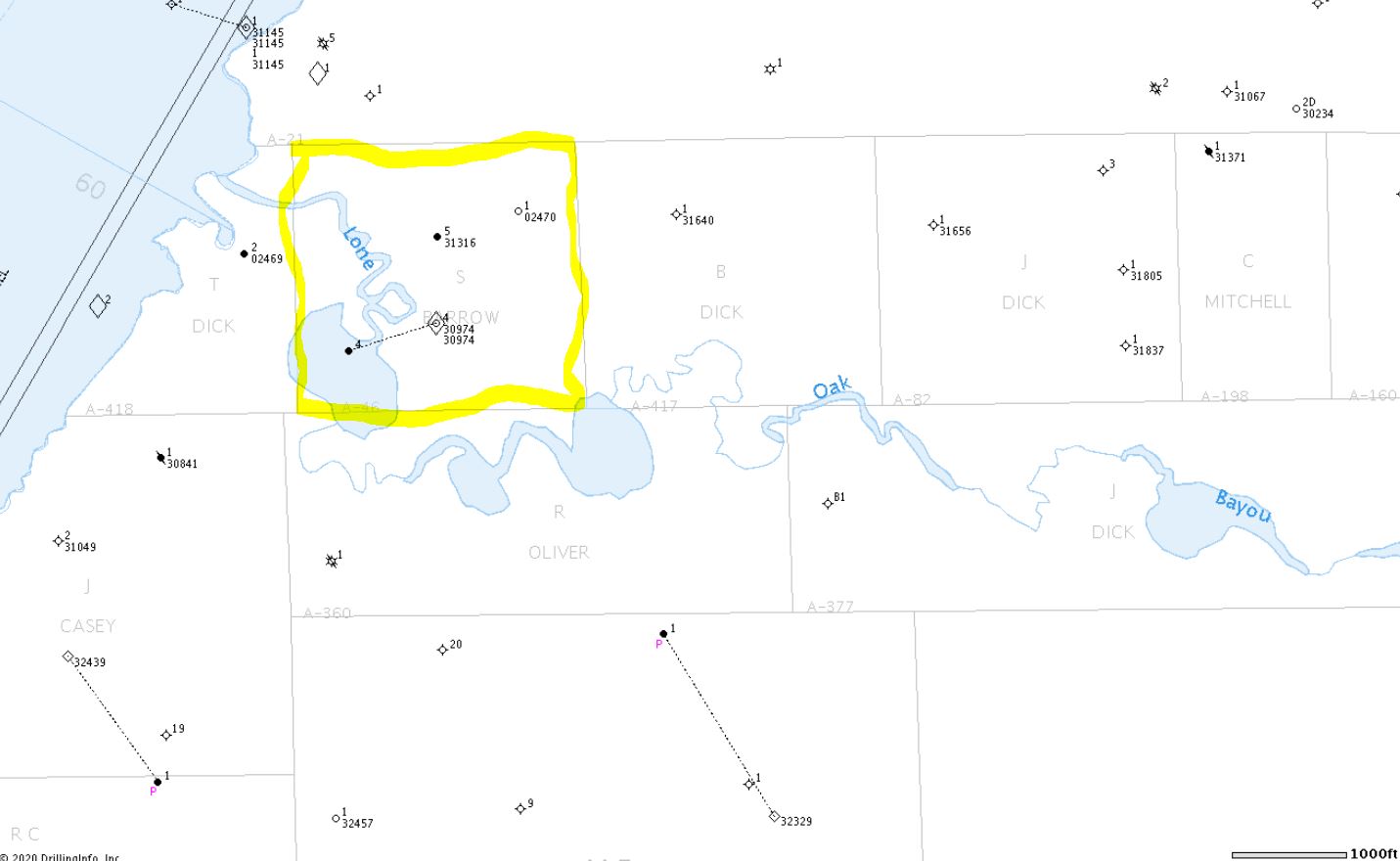

Lone Oak Club, a hunting and fishing club, owns a tract of land in Galveston County near Galveston Bay, through which runs Lone Oak Bayou:

Members of the public boat up into Lone Oak Bayou and sometimes wade and fish or hunt in its shallow waters. Lone Oak complained about this activity and asserted that it owns the bed of Lone Oak Bayou and that members are trespassing when they set foot on the bayou’s bed. The Club agrees that the public has the right to boat on the public waters of the bayou, but when the fisherman or hunter steps out of his boat, they claimed trespass. The Texas General Land Office disagreed. It said the State owns the bed of Lone Oak Bayou adjacent to the Club’s land because the bayou is influenced by tides from the bay and is below the line of mean high tide, and the State owns all submerged lands within tidewater limits. So the Club sued George P. Bush, Commissioner of the Land Office, to establish its title to the bed of the bayou within the boundaries of its 160 acres.

Members of the public boat up into Lone Oak Bayou and sometimes wade and fish or hunt in its shallow waters. Lone Oak complained about this activity and asserted that it owns the bed of Lone Oak Bayou and that members are trespassing when they set foot on the bayou’s bed. The Club agrees that the public has the right to boat on the public waters of the bayou, but when the fisherman or hunter steps out of his boat, they claimed trespass. The Texas General Land Office disagreed. It said the State owns the bed of Lone Oak Bayou adjacent to the Club’s land because the bayou is influenced by tides from the bay and is below the line of mean high tide, and the State owns all submerged lands within tidewater limits. So the Club sued George P. Bush, Commissioner of the Land Office, to establish its title to the bed of the bayou within the boundaries of its 160 acres.

Nature sometimes does not cooperate with the laws created by humans to establish the boundary between the land and water. In Texas especially these laws, mostly created by courts, can sometimes be confusing and complex. Water boundaries shift with the rise and fall of tides, erosion and evulsion, and changes in watercourses. I learned this when I was asked, in my first year of law practice many years ago, to summarize Texas laws regarding land boundaries and rights of public access for a client who owned land along the coast.

In Bush v. Lone Oak Club, the Court ruled partly for the Club but remanded the case for further fact findings. The Court was divided 6-2, with one judge abstaining. Justice Busby delivered the majority opinion, and Justice Green wrote a dissent joined by Chief Justice Hecht.

The question the Court disagreed on was whether the Small Bill granted the bed of Lone Oak Bayou to the Club. Now Tex.Rev.Civ.Stat. art. 5141a(1), the Small Bill was passed by the Legislature in 1929, named after Clint Small, the state senator from Austin. The purpose of the bill was to address an issue complained of by landowners whose land was crossed by a river or stream. That issue arose because of a statute passed by the Republic of Texas in 1837, called the Navigable Stream Statute, now Tex. Nat.Res. Code Section 26.001(c). That statute, in turn, was passed because, under Spanish civil law (remember Texas did not adopt the common law system until 1840) the beds of navigable streams belong to the State, and it was difficult to determine what streams and rivers in Texas were navigable. So the Texas Congress declared that any stream is navigable so long as it maintains an average width of 30 feet or more from the mouth up, measured from bank to bank. The statute also prohibited surveys of land to be sold by the State from crossing over navigable streams. Such grants had to front on, but not include, the bed of a navigable stream.

But many land grants did cross over streams declared by the Navigable Stream Statute to be navigable. The patent purported to grant the bed of the stream to the buyer, and the buyer paid for that submerged land, but the statute declared that bed to be owned by the State. Landowners were unhappy. So the Legislature passed the Small Bill. It granted to those landowners title to the bed of the stream crossing their grant if they had paid for the land within the bed at the time of the grant. Lone Oak Club claimed that, under the terms of the Small Bill, it owned the bed of Lone Oak Bayou.

The Land Office argued that the Small Bill does not apply to submerged lands “within tidewater limits”. There was no dispute that the water level in Lone Oak Bayou as it crossed the Club’s lands rises and falls with the tides. Under the common law adopted by Texas, the State retains title to all submerged lands below the line of “mean high tide.” The Land Office contended that it was never the intent of the Legislature in the Small Bill to affect title to lands that legally are part of the bed of the sea. So that question was debated in the two opinions issued by the Court, the majority finding that the Small Bill does apply to lands within tidewater limits, the dissent arguing that it does not. A lot of legal jousting over whether a fisherman can wade in the waters of Lone Oak Bayou adjacent to the lands of Lone Oak Club.

Actually, this case may affect large sections of land along the Gulf Coast. Below is a picture from Google Earth of the lands around the tract owned by Lone Oak Club. The land is flat and marshy and tides influence the ebb and flow of water in these marshes. It is often impossible to tell where the land ends and the water begins. (Click on image to enlarge.)

The Land Office made a second argument in Lone Oak. It argued that Lone Oak had failed to prove as a matter of law that Lone Oak Bayou is a stream to which the Small Bill applies. The trial court had ruled as a matter of law on summary judgment that the boyou was a stream and the Small Bill applies. But the Supreme Court held that the summary judgment created only a fact issue, and it remanded the case for evidence on whether the bayou is a navigable stream:

To constitute a “stream” or “water course” and calculate its gradient boundary, Lone Oak Bayou must have banks. … The Club has not proven this to be the case. The Club’s evidence concerning the presence of banks includes a surveyor affidavit stating that “in certain areas Lone Oak Bayou has a defined bank.” But the bayou has also “been described as a marsh, for which no banks exist,” and for which “a gradient boundary cannot be determined.”

The boundary between the sea and the land marks not only the line between the State’s ownership of the seabed and private upland, but also the line of the State’s ownership of minerals under submerged land. Texas owns title to minerals under the Gulf of Mexico extending three marine leagues from the shore. But a large portion of Texas’ submerged lands lie within the Laguna Madre, the “mother lagoon” lying between Padre Island and the mainland, stretching from Brownsville to Matagorda Bay. The difficulties in finding the line between land and sea are illustrated by a case over title to a portion of the bed of the Laguna Madre known as the “land cut.”

Laguna Madre is in most places very shallow, two feet or less in depth. Wind-driven tides cause huge areas of the laguna to be sometimes dry, sometimes inundated. The Intracoastal Waterway, constructed by the US Army Corps of Engineers in the 1930’s, runs the length of the laguna and allows for navigation.

One area of the laguna, called the land cut, located in Kenedy County, is often totally exposed from the mainland to Padre Island. It serves to separate the northern and southern segments of the Laguna Madre. In some seasons of the year it is covered with water – in other seasons it is dry mud flats. Below is an image from Google Earth of the land cut. The entire area encompasses about 35,000 acres of land.

Beginning in about 1996, our firm represented the Texas General Land Office in a dispute with the John G. and Marie Stella Kenedy Memorial Foundation over title to the land cut. The John G. and Marie Stella Kenedy Memorial foundation v. Dewhurst, Commissioner, 90 S.W.3d 268 (Tex. 2002). The Kenedy Foundation owns the lands to the west of the land cut, given to the Foundation by Sarita Kenedy East. The Ranch encompasses some 235,000 acres, one of the largest ranches in Texas. The Foundation argued that the land cut was dry land and part of the original Spanish and Mexican grants making up the Kenedy Ranch. The State argued that the land cut – sometimes dry, sometimes inundated – was part of the bed of the Laguna Madre, owned by the State. The fight, of course, was not over the land, a vast mud flat wasteland, but over the mineral rights to 35,000 acres along the Texas Gulf Coast.

After a jury trial, the trial court entered judgment holding that the State owned the disputed land as submerged land within the Laguna Madre. That judgment was upheld by the Austin Court of Appeals. In December 2000, the Texas Supreme Court affirmed. But the Kenedy Foundation asked the Court to reconsider, and in 2001 the Court agreed to rehear the case. During the interim, several supreme court seats on the court changed hands. Finally, on August 29, 2002, the Court withdrew its prior opinion and issued an opinion reversing the courts below and holding that the entire disputed area belongs to the Foundation. Three justices dissented.

The Foundation claimed title to the land to the western edge of the Intracoastal Waterway, which it contended is the present boundary between land and sea. So that is where the boundary is today. As a result of the Kenedy case the map of the Kenedy Ranch as now shown on its website looks like this:

In effect, the Court ruled that the “shore” of the Laguna Madre adjacent to the Kenedy Ranch lies along the edge of the Intracoastal Waterway, a man-made channel.

Another example of humans’ efforts to draw lines upon nature.

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog