Pending before the Texas Supreme Court is the petition for review of Ammonite Oil & Gas Corporation challenging the decision of the San Antonio Court of Appeals in Ammonite Oil and Gas Corp v. Railroad Comm’n of Texas, 2021 WL 4976324 (Oct. 27, 2021). The Court of Appeals upheld the RRC’s decision to deny Ammonite’s sixteen applications to force-pool portions of the Frio River into pooled units created by EOG for its horizontal wells in the Eagleville (Eagle Ford-1) Field in McMullen County. The application presents several interesting issues regarding the scope and interpretation of the MIPA.

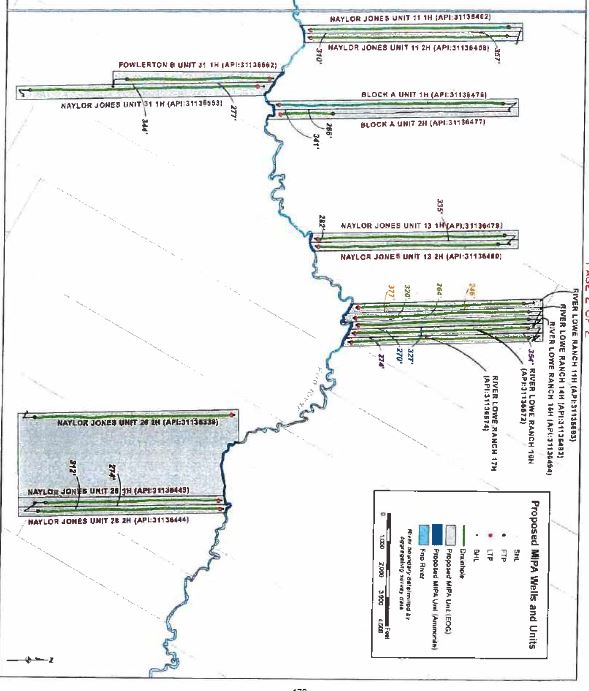

The State of Texas owns the land within Texas riverbeds. Ammonite leased the oil and gas in the Frio River from the Texas General Land Office. Ammonite then made an offer to EOG to pool adjacent portions of the riverbed into sixteen existing EOG units along the river. (click on image to enlarge) Ammonite offered to sign an operating agreement with EOG providing for Ammonite to pay its share of costs related to wells in the pooled unit, based on its share of the acreage in the unit. It also offered a 10% “risk penalty.” Ammonite would agree that EOG could recover 110% of its already-incurred costs for wells on the unit before Ammonite would receive its share of revenues from the wells.

Ammonite offered to sign an operating agreement with EOG providing for Ammonite to pay its share of costs related to wells in the pooled unit, based on its share of the acreage in the unit. It also offered a 10% “risk penalty.” Ammonite would agree that EOG could recover 110% of its already-incurred costs for wells on the unit before Ammonite would receive its share of revenues from the wells.

EOG rejected Ammonite’s offers and did not make any counteroffer.

The Mineral Interest Pooling Act, Chapter 102 of the Texas Natural Resources Code, allows the owner of a tract adjacent to an existing pooled unit to “muscle in” to the unit if certain requirements are met. The Act was passed to prevent minerals underlying small, irregularly shaped tracts from being wasted by production from adjacent wells. It is designed to encourage owners to agree to pooling by requiring owners to negotiate in good faith for a voluntary unit. The party desiring its acreage to be added to the unit must first make a “fair and reasonable offer” to the unit operator for pooling. If the operator refuses, the party seeking pooling can then file an application with the RRC to force pool the tract under the MIPA. Ammonite filed sixteen MIPA applications with the RRC to muscle into EOG’s units with portions of the bed of the Frio River.

Ammonite’s applications were heard before two RRC administrative law judges. They issued a Proposal for Decision recommending that fifteen of Ammonite’s applications be granted. The three Railroad Commissioners overruled the ALJs and denied all of Ammonite’s applications. The San Antonio Court of Appeals affirmed.

EOG made several arguments to defeat Ammonite’s applications.

- EOG argued that Ammonite had not made a “fair and reasonable offer” as required by the MIPA.

- EOG contended that Ammonite had to show that EOG’s wells would drain the oil and gas under the Frio River as a condition to forced pooling under the MIPA.

- EOG argued that the applications should be denied because Ammonite had not provided surveyed legal descriptions of the riverbed acreage to be added to its units.

- EOG argued that requiring it to include the riverbed tracts in its units would constitute a taking of its property in violation of the US Constitution.

The ALJs disagreed with EOG’s arguments. They determined that proof of drainage was not a requirement of the MIPA, only proof of “waste.” Waste would occur because without forced pooling the State would never benefit from the minerals under the river, thus denying the State its correlative rights. “While the existence of drainage may be some evidence of a common reservoir and of a fair and reasonable offer, especially in a conventional reservoir context, there is ample evidence in the record to show that the absence of drainage should not be [a] one-dimensional litmus test for the success of a MIPA pooling application in the Eagle Ford Shale trend or the Eagleville (Eagle Ford-1) Field.” “Compulsory pooling as proposed by Ammonite, enabling such current or future wells to produce from such undrained acreage, both on EOG’s acreage and the Frio Riverbed tracts, is the only way to prevent waste and to permit all owners to have their fair share of hydrocarbons produced from the common reservoir in this case.”

The ALJs then considered EOG’s argument that the 10% risk penalty offered by Ammonite was insufficient and that the risk penalty should be 100%. The ALJs discussed the evidence and concluded that a reasonable risk penalty would be 50%. Under the MIPA, the RRC can set the appropriate risk penalty, between 0% and 100%. Ammonite’s applications stated that it would accept whatever risk penalty was considered appropriate by the RRC.

Finally, regarding EOG’s takings argument, the ALJs said EOG “ignores the fact that valuable riverbed mineral acreage is being contributed to each unit for production and development … and that the benefits thereof will be allocated on an acreage basis, a well-established and fair method of doing so. Hence, formation of the MIPA units involves the exchange of valuable consideration in the same way parties do when dealing at arms-length.”

In denying Ammonite’s application and overruling the ALJs, the three Commissioners concluded that:

- “The applicant failed to meet its burden of proof to prove that the granting of the application is necessary to prevent waste, protect correlative rights, or avoid the unnecessary drilling of wells.”

- “Ammonite failed to make a fair and reasonable offer to voluntarily pool …”

The Court of Appeals affirmed, holding that the RRC’s conclusion that Ammonite had failed to make a fair and reasonable offer to voluntarily pool.

The Commission’s conclusion was based on its factual findings that: Ammonite failed to provide survey data or a metes and bounds description of the riverbed to establish the precise acreage to be pooled (Finding of Fact #6); none of the EOG’s sixteen wells produce hydrocarbons from or drain Ammonite’s riverbed tracts (Finding of Fact #7); and Ammonite agreed that a greater charge for risk than the 10% listed in its voluntary pooling offers was reasonable (Fact Finding #8). Upon review, the district court determined that the Commission’s fact findings were supported by more than a scintilla of evidence in the administrative record and affirmed. We must determine whether the record contains substantial evidence to support the Commission’s findings and conclusion regarding Ammonite’s voluntary pooling offers.

***

We conclude there is a reasonable basis for the Commission’s fact finding and conclusion that Ammonite’s voluntary pooling offers were not fair and reasonable based on a 10% charge for risk being unreasonably low according to Smith’s uncontroverted testimony. Substantial evidence supports the Commission’s decision and its dismissal of Ammonite’s MIPA applications for lack of jurisdiction. We therefore do not reach Ammonite’s other issues on appeal.

Neither the RRC’s order nor the Court of Appeals’ opinion, unlike the ALJ’s proposal for decision, provide any discussion of the prior legal precedent relied on by the ALJs, or of whether proof of drainage is necessary to muscle into a unit under the MIPA, or of why granting the applications would not prevent waste. The RRC’s order makes no mention of the fact that the ALJs recommended a 50% risk penalty to which Ammonite had agreed, or whether such a risk penalty would be fair and reasonable.

The Court of Appeals’ decision appears to be based on the RRC’s conclusion that a 10% risk penalty would not be fair and reasonable; but nothing in the RRC’s order says that the 10% penalty offered by Ammonite, or the 50% penalty recommended by the ALJs, would not be fair and reasonable. Instead, the RRC’s conclusion was that “[b]ecause the applicant failed to meet its burden of proof to prove that the granting of the application is necessary to prevent waste, protect correlative rights, or avoid the unnecessary drilling of wells, the necessary pre-requisites for MIPA pooling have not been established. Ammonite’s applications for all sixteen (16) units must be denied.” Yet the Court of Appeals never discusses whether proof of drainage is necessary to muscle into a pooled unit or whether denying the applications would cause waste.

The Supreme Court has not yet acted on Ammonite’s petition for review.

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog