On February 2, 1848, the United States and Mexico signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ending the Mexican-American War. I’ve been reading the biography of Stonewall Jackson; he and many of the generals in the Civil War first experienced combat in that war. As part of the treaty Mexico ceded the portion of Texas between the Nueces and Rio Grande Rivers, and Texas and the U.S. recognized the validity of titles to land granted by Mexico and Spain in this area, known as the Nueces Strip.

Of course the treaty didn’t settle matters in the Nueces Strip. In 1850 a movement arose to establish a Rio Grande territory separate from Texas. Its leaders called for a convention to form a provisional government and a petition to Congress to recognize the area as a separate territory. Part of the reason for the movement was fear that Texas wouldn’t recognize their land titles.

In response, on February 22, 1850, the Texas Legislature passed a law establishing a commission to investigate and recommend for confirmation title claims emanating from Spanish and Mexican land grants. Known as the Bourland Commission, it consisted of two commissioners, William Bourland and James Miller, and Robert Jones, a well-known lawyer and judge, to serve as the commission’s attorney. The commissioners gathered evidence, including documents, affidavits and testimony, and prepared an abstract on each claim and a recommendation as to whether the claim should be confirmed or rejected. The legislature then acted to confirm or deny applications for recognition of the land titles.

The commissioners heard evidence in Laredo, Brownsville, Eagle Pass, Rio Grande City and Corpus Christi in 1850 and 1851. During his travels Miller took a voyage from Port Isabel to Galveston on the steamer Anson. On the second day of the voyage the Anson sank in a storm. Miller survived but he lost his trunk which contained original titles submitted by land claimants, among them original Spanish and Mexican documents obtained from Mexico. As a result the Commission had to redo much of its work, relying on affidavits and copies of documents.

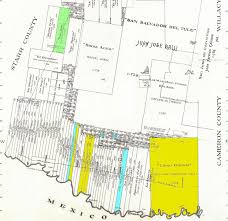

On February 10, 1852 the legislature confirmed 234 claims in the names of the original Spanish and Mexican grantees and their heirs and purchasers, following the commissioners’ recommendations. The legislature also confirmed several claims the commissioners refused to recommend, including those for the Llano Grande and Las Mestenas grants in Hidalgo County, belonging to the Hinojosa and Balli families, and the San Salvador del Tule Grant, one of the largest grants in Texas. Seventy additional grants were later adjudicated, and many other claims were separately tried in court proceedings under laws enacted as late as 1901.

Although the adjudication of titles after the war was quick and favored Mexican land tenure, later actions by Anglos deprived many Mexican owners of their title by dubious means, and controversies over Spanish and Mexican titles have continued. Most recently, in 2013 the legislature created the Texas Unclaimed Mineral Proceeds Commission in response to claims by Hispanic citizens that vast amounts of money were being held as unclaimed mineral proceeds by the Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts that should belong to descendants of Spanish and Mexican land grant recipients. I wrote about this commission’s work in 2015. It concluded that there was no basis for such claims.

Under the treaty, Texas law regarding titles to land granted by Spain and Mexico is determined by the laws in effect on the date of the grant. As a result, Texas title attorneys must be familiar with Mexican and Spanish laws in effect when the grants were made, including those related to water and mineral rights and littoral boundaries.

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog