Last week the Texas Supreme Court handed down its decision in Ammonite v. Railroad Commission, upholding the Commission’s denial of Ammonite’s MIPA application. Justice Young filed a dissenting opinion, joined by Justice Busby. The case has little implication for most mineral owners in Texas but is an important loss for the State of Texas and an important decision for future MIPA applications.

The State of Texas owns the lands within the beds of navigable rivers and waterways, some 80,000 miles of rivers and streams. Where oil and gas development occurs adjacent to rivers, operators often lease those riverbeds and include them in pooled units. Revenues from leasing of State lands goes to the State’s permanent school fund, which funds primary education. But EOG Resources, developing horizontal wells in the Eagle Ford Shale along both sides of the Frio River, decided not to lease the State’s riverbed, and left it out of the units.

Ammonite Oil & Gas, owned by William Osborn (my first cousin) leases riverbeds and stranded State tracts from the General Land Office and works to get them included in adjacent pooled units. If it is unable to reach agreement Ammonite files an action under the MIPA.

The Mineral Interest Pooling Act (MIPA), Texas Natural Resources Code Chapter 102, provides a procedure by which stranded tracts can be “force-pooled” into existing units. To take advantage of the statute the owner or lessee of the stranded tract must first make a “fair and reasonable offer” to pool the tract. If no agreement is reached, the owner or lessee of the stranded tract can then file an application under the MIPA with the Commission.

In an MIPA action the Commission first determines whether the applicant has made a “fair and reasonable offer” to include its tract in the unit. If it concludes that a fair offer was made, it then must determine whether the application should be granted “for the purpose of avoiding the drilling of unnecessary wells, protecting correlative rights, or preventing waste.” If it so concludes, then the Commission “shall” order pooling.

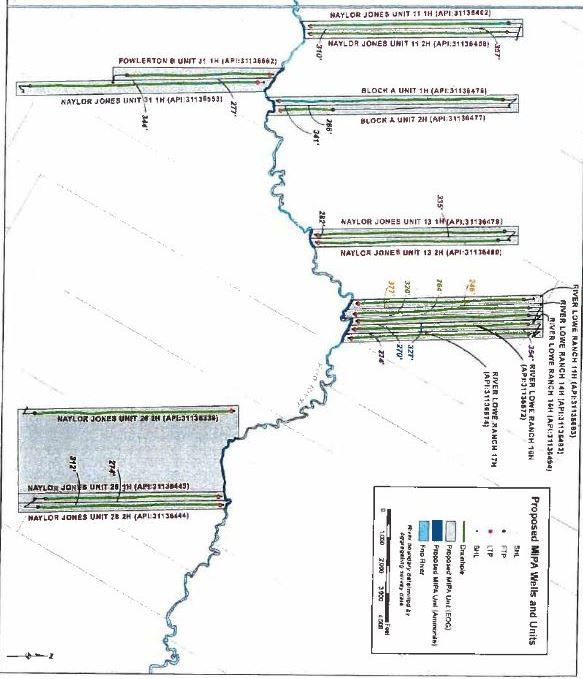

In 2015, Ammonite acquired a lease on the Frio riverbed adjacent to EOG’s wells, a strip some 30 feet wide and seven miles long, about 21 acres. The State reserved a 25% royalty. Ammonite then made written offers to EOG to include portions of its lease in 16 pooled units for 16 wells then permitted or being drilled. Ammonite proposed that its lease would be allocated a share of production based on acreage – about 1% of each unit – and that Ammonite would pay its share of drilling, completion and operating costs, plus a 10% “risk penalty” – an additional 10% of those costs to compensate EOG for its risk in drilling and completing the wells – “or such greater penalty as may be prescribed by the Railroad Commission if an MIPA case should have to be adjudicated before that agency.” The MIPA provides that an applicant “may” be assessed a risk penalty as a condition to being pooled.

After EOG refused to negotiate with Ammonite, it filed 16 MIPA actions at the Commission seeking pooling of its riverbed lease. The actions were consolidated and its case was presented before administrative law judges at the Commission. At the hearing, Ammonite did not contend that EOG’s wells would drain oil or gas from beneath the riverbed, but it argued that it was entitled to have its acreage pooled because pooling would prevent waste. EOG contended that Ammonite was not entitled to relief because Ammonite had not made a fair and reasonable offer to pool and because EOG’s wells do not drain the riverbed.

The administrative law judges issued a proposal for decision recommending that all but one of Ammonite’s applications be granted. They recommended a 50% risk penalty. But the Commission refused to accept the ALJ’s recommendation and denied Ammonite’s applications. Ammonite appealed, and the 4th Court of Appeals affirmed the Commission, holding that Ammonite had not made a fair and reasonable offer to pool. The Supreme Court affirmed, but on different grounds.

Justice Young wrote a strong dissent, with which I agree. He would reverse and remand either to the Court of Appeals or to the Commission for further proceedings. He would hold that Ammonite had made a fair and reasonable offer to pool, and that the Commission had not sufficiently explained its conclusion that pooling would not prevent waste.

Justice Young argues that the majority opinion (by Chief Justice Hecht) confuses the MIPA’s requirement of a fair and reasonable offer with its requirement that the pooling would protect correlative rights or prevent waste; and he disagrees with the majority’s conclusion that, for Ammonite to succeed, it must show that the riverbed will be drained by EOG’s wells.

[W]hile drainage would be dispositive of whether forced pooling could properly protect correlative rights, Ammonite requests forced pooling (at least in part, if not wholly) for the distinct … “purposes” of “preventing waste”—not of minerals that will be drained, but of minerals that will be stranded. The Commission and this Court mistakenly treat Ammonite’s applications as resting solely on “drainage” and “protecting correlative rights” when it is waste through stranding that matters.

***

We should make sure that, when the Commission [considers the facts in an MIPA case], it does not rely on the erroneous impression that “no drainage” is alone a sound basis to deny the pooling applications. The lack of drainage is the very thing that allegedly makes the minerals here stranded. If they are stranded, they constitute waste. And if there is waste, then pooling is on the table and is sometimes mandatory. Drainage is not and never has been required to establish “waste”.

Justice Young criticizes the Commission for not making factual findings based on the evidence produced at the hearing. The Commission’s only “finding” regarding waste was that “compulsory pooling will not prevent waste.”

[T]he Commission did not articulate why it could not order forced pooling to prevent wasting Ammonite’s stranded minerals. Texas administrative law requires sufficient explanations of administrative actions before courts can uphold them. This requirement, which ensures that agencies’ actions are always based on the law and the facts, protects both the agencies themselves and the regulated public.

***

[C]ourts must “insist that an agency examine the relevant data and articulate a satisfactory explanation for its action.” FCC v. Fox Television Stations, Inc., 556 U.S. 502, 513 (2009).

Justice Young also criticizes the majority opinion for addressing whether Ammonite made an adequate showing that pooling would prevent waste, an issue not addressed by the Court of Appeals; it is substituting the Court’s own judgment for an issue that should have first been addressed by the Commission.

In other words, “upholding” a Commission order on grounds that the Commission never explained and may not even agree with hardly reflects deference [to the administrative agency].”

The Court’s decision also is another instance of its rulings against the General Land Office (and therefore against the interests of the permanent school fund). In John G. and Marie Stella Kenedy Memorial Foundation v. Dewhurst, 90 S.W.3d 268 (Tex. 2002) the Court held that 34,000 acres of land within the Laguna Madre, between the mainland and Padre Island, was not submerged land belonging to the State of Texas. In Brainard v. State, 12 S.W.3d 6 (Tex. 1999) the Court deprived the State of title to substantial lands in the bed of the Canadian River because a dam built upstream changed the width of the river. (Our firm represented the State in both cases.)

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog