I recently ran across a publication containing two stories by O. Henry, purchased at the Capitol Visitors Center in Austin. The stories center on the Texas General Land Office, where O. Henry (then William Sydney Porter) worked as a draftsman between 1887 and 1891. The stories led me down a rabbit hole of the history of the Texas General Land Office.

The General Land Office is the oldest Texas state agency, established by the Republic of Texas in 1836 to “superintend, execute, and perform all acts touching or respecting the public lands of Texas.” When Texas entered the Union in 1845, the United States allowed it to keep its public lands rather than taking those lands in exchange for assuming Texas’ public debt. The GLO was responsible for granting patents as land was settled and sold. The history of land grants in Texas is complex and colorful, including Spanish and Mexican land grants in South Texas and to Stephen F. Austin and other empresarios who settled the land before Texas independence. The records of those Spanish and Mexican land grants, and all other grants and surveys of state lands, are housed in the General Land Office. Many of those records, including historical maps and surveys, have been digitized and can be viewed online at the GLO website.

After Texas won its independence from Mexico, Columbia became the nation’s capital and its archives were housed there. The records were moved to Houston when Congress declared Houston the capital of Texas in 1836. Then in 1839, then-President Mirabeau B. Lamar convinced Congress to authorize the establishment of a planned city, Austin, to be the nation’s capital, and the archives were moved there.

In 1842 Mexican troops invaded Texas and 1,000 Mexican troops camped outside San Antonio. Although they retreated after a few days, Sam Houston, who had been re-elected President, ordered the Secretary of War George Washington Hockley to move the archives to Houston. But the citizens of Austin formed a committee who concluded that moving the archives would violate the law. In September 1842 another Mexican military expedition into Texas resulted in the temporary capture of San Antonio. Houston again convened Congress and demanded that the archives be moved to Houston; but Congress, divided on the issue, failed to act. So Houston took matters into his own hands and tasked Colonel Thomas Smith to move the archives to Washington-on-the Brazos. Smith, with 20 men and three wagons, moved into Austin on the night of December 30, 1842 to take possession of the archives. As they were loading the wagons, Angelina Eberly, owner of a nearby boardinghouse, spied them and ran to Congress Avenue where a six-pound cannon was located. She fired it at the General Land Office. Although there were no damage or injuries, Smith and his men left quickly with the records. A group of Austin citizens followed and overcame Smith’s entourage, recovered the records, and returned them to Austin on December 31, 1842. The incident is known as the Texas Archive War. But Houston continued to convene the government in Washington-on-the-Brazos until Texas was annexed into the Union in 1845.

A statue of Angelina Eberly firing the cannon, designed by Pat Oliphant, resides on Congress Avenue in Austin.

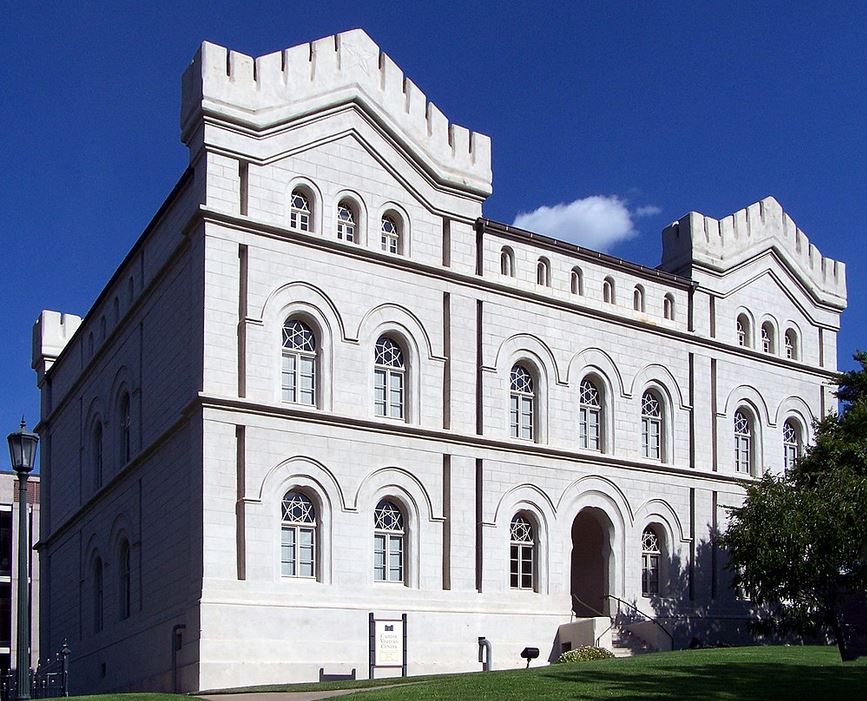

A building to house the Texas archives, completed in 1857, is the oldest surviving state office building in Texas. It was designed by a German architect, Christoph Conrad Stremme. It functioned as the state’s land office until 1917, when the Commission moved to a larger building. It now serves as the Capitol Visitors Center and is on the National Register of Historic Places. Worth a visit.

The Texas General Land Office has its own colorful history. The Commissioner of the Land Office is a state-wide elected office, and the office has been held by many famous and infamous characters. One such is Bascom Giles, Commissioner from 1939 to 1955. He is remembered for his role in the Veterans Land Board scandal.

Giles first worked at the GLO as a draftsman. First elected in 1939, he was reelected eight times. In 1946, Texas created the Texas Veterans Land Board and appropriated $100 million to loan money to Texas veterans to buy land for 5% down, low interest, and 40 years to pay off the balance. He was found to be involved in a scheme to defraud veterans. The reporter who uncovered the fraud won the Pulitzer Prize for his reporting, and Giles was convicted of fraud and bribery and served three years of a six-year prison term.

Giles’ successor as Commissioner was James Earl Rudder. Rudder commanded the historic Pointe du Hoc battle during the invasion of Normandy; his army rangers scaled 100-foot cliffs under enemy fire and destroyed a German gun battery, suffering more than 50% casualties. He also led a series of actions during the Battle of the Bulge.

Rudder became the President of Texas A&M University in 1959 and was president of the A&M System from 1965 until his death in 1970. During his tenor he transformed A&M to a modern university. He made membership in the Corps of Cadets optional, allowed women to attend, and led efforts to integrate the campus. A&M is now the largest university in the US by enrollment.

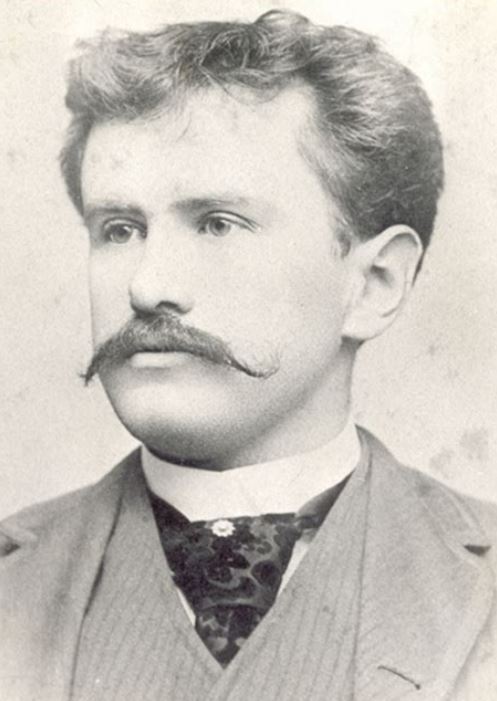

William Sydney Porter was born near Greensboro, North Carolina in 1862. In 1882 he moved to Cotulla, Texas and worked on a ranch as a sheep herder. He moved to Austin in 1884, where he held several jobs, including as a pharmacist and selling cigars in the Driskill Hotel—and, a stint as a draftsman in the General Land Office. Porter met Athol Estes, fell in love, and they eloped in 1887 and were married in the home of Reverend R. K. Smoot–a home that still stands on West Sixth Street in Austin. A daughter, Margaret, was born in 1889.

William Sydney Porter was born near Greensboro, North Carolina in 1862. In 1882 he moved to Cotulla, Texas and worked on a ranch as a sheep herder. He moved to Austin in 1884, where he held several jobs, including as a pharmacist and selling cigars in the Driskill Hotel—and, a stint as a draftsman in the General Land Office. Porter met Athol Estes, fell in love, and they eloped in 1887 and were married in the home of Reverend R. K. Smoot–a home that still stands on West Sixth Street in Austin. A daughter, Margaret, was born in 1889.

The Porters lived in a house in downtown Austin between 1883 and 1895. It is now the O. Henry Museum. For 48 years the museum has held its annual O. Henry Museum Pun-Off competition in May of each year.

In 1891 Porter was hired as a teller at the First National Bank of Austin. Federal bank examiners found that funds were embezzled by corrupt bank managers, Porter was implicated, arrested, and released on bail. But rather than stand trial he fled to Honduras. He returned to Austin after learning that his wife was dying of tuberculosis. She died in 1897, and Porter was convicted in 1898 and sentenced to five years in federal prison in Columbus, Ohio. It was there that Porter assumed the pen name O. Henry and wrote the stories that made him famous, including “The Gift of the Magi” and “The Ransom of Red Chief.” After three years in prison Porter moved to New York, never returning to Texas. Not until after his death did historians connect O. Henry to the William Sydney Porter who had been convicted of embezzlement.

All of which leads us to O. Henry’s “Stories of the Old Land Office.” The first story is “Bexar Scrip No. 2692,” in which he recounts how a “land shark” steals land from a widow and her son by absconding with land office records and in the course of that caper killing the son, on the land office premises. If O. Henry is to be believed, skullduggery in the land office was common in those days:

Volumes could be filled with accounts of the knavery, double-dealing, the cross purposes, the perjury, the lies, the bribery, the alterations and erasing, the suppressing and destroying of papers, the various schemes and plots that for the sake of the almighty dollar have left their stains upon the records of the General Land Office.

The second story, “Georgia’s Ruling,” concerns vacancy hunters. Before one applied for a patent—a deed from the state—one first had to hire a surveyor to survey the land. According to O. Henry, surveyors in the old days were not too careful in their craft.

In those days-and here is where the trouble began-the State’s domain was practically inexhaustible, and the old surveyors, with princely-yea, even Western American-liberality, gave good measure and overflowing often the jovial man of metes and bounds would dispense altogether with the tripod and chain. Mounted on a pony that could cover something near a “vara” at a step, with a pocket compass to direct his course, he would trot out a survey by counting the beat of his pony’s hoofs, mark his corners, and write out his field notes with the complacency produced by an act of duty well performed. Sometimes-and who could blame the surveyor?-when the pone was “feeling his oats,” he might step a little higher and farther, and in that case the beneficiary of the scrip might get a thousand or two more acres in his survey than the scrip called for. … Nearly every old survey in the State contained an excess of land.

Vacancy hunters found surveys with such excess acreage and would file applications for the award of the “vacancy” to them. In the process settlers who obtained the original patent were sometimes dispossessed. In “Georga’s Ruling” vacancy hunters sought to claim a vacancy that would displace many homeowners. But in a happy twist, the Commissioner rules against them, finding there is no vacancy despite the excess acreage.

The Commissioner’s ruling in the story, Georgia’s ruling, is actually a well-established rule of surveying, known as the Priority of Calls. The survey in question in O. Henry’s story called for a certain course and distance from a known survey marker to a river. But the distance called for was a mile short of the actual river. The order of priority of calls says that, in reconstructing a survey, the highest priority is given to calls for natural monuments—such as rivers and trees; then artificial monuments, such as stakes or rock piles; then to distances of linear measurement. Georgia’s ruling was that the surveyor’s call for the edge of the river took priority over his call for the distance to the river. So O. Henry knew that of which he was speaking.

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog