Last Tuesday the Texas Supreme Court heard arguments in three cases on oil-and-gas-related topics.

Murphy Oil v. Adams, No. 16-0505:

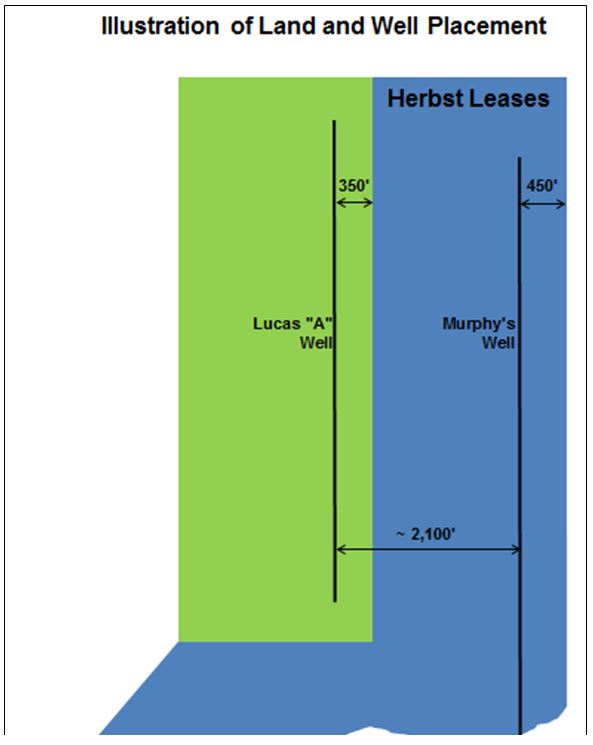

Our firm represents the Herbsts in this case. Murphy owns a lease on their lands in Atascosa County, shown in blue below. While the Herbst Lease was in its primary term, Comstock drilled the Lucas A Well on the adjacent tract, shown in green.

The Herbst lease contains the following provision:

The Herbst lease contains the following provision:

It is hereby specifically agreed and stipulated that in the event a well is completed as a producer of oil and/or gas on land adjacent and contiguous to the leased premises, and within 467 feet of the premises covered by this lease, that Lessee herein is hereby obligated to, within 120 days after the completion date of the well or wells on the adjacent acreage, as follows:

(1) to commence drilling operations on the leased acreage and thereafter continue the drilling of such off-set well or wells with due diligence to a depth adequate to test the same formation from which the well or wells are producing from on the adjacent acreage; or

(2) pay the Lessor royalties as provided for in this lease as if an equivalent amount of production of oil and/or gas were being obtained from the off-set location on these leased premises as that which is being produced from the adjacent well or wells; or

(3) release an amount of acreage sufficient to constitute a spacing unit equivalent in size to the spacing unit that would be allocated under this lease to such well or wells on the adjacent lands, as to the zones or strata producing in such adjacent well.

After the Lucas A well was completed, Murphy drilled its well on the Herbst Lease, shown above, 2100 feet from the Lucas A well. Murphy claims its well satisfies the above-quoted lease provision. The Herbsts claim it does not.

ConocoPhillips v. Koopman, 16-0662

One of the issues in this case is whether the reservation of a term royalty interest in a deed of land violates the Rule Against Perpetuities. The deed reserved the following interest:

There is excepted from this conveyance and reserved to the Grantor and her heirs and assigns for the term hereinafter set forth one-half of the royalties from the production of oil, gas, casinghead gas, gasoline, distillate, condensate, … and all other minerals, …. in, on and under the herein conveyed land, which reserved royalty interest is a non-participating interest and is reserved for the limited term of 15 years from the date of this Deed and as long thereafter as there is production in paying or commercial quantities …

Conoco acquired a lease on the lands conveyed by the deed. While the lease was in its primary term, the owner of the reserved royalty interest contacted Conoco, telling it that her term royalty was about to expire and requesting that Conoco drill a well to preserve the term royalty. To induce Conoco to drill the well, the term royalty owner conveyed a portion of her term royalty to Conoco. Conoco drilled a well but failed to get it completed and commence production before expiration of the 15-year term. This suit ensued.

As one of its arguments, Conoco claims the term royalty violates the Rule Against Perpetuities. This rule, as explained in Wikipedia, is

a rule in the common law that forbids legal instruments (usually a will) from tying up property for too long a time beyond the lives of people living at the time the instrument was written. Specifically, the rule forbids a person from creating future interests (traditionally contingent remainders and executory interests) in property that would vest at a date beyond that of the lifetimes of those then living plus 21 years. In essence, the rule prevents a person from putting qualifications and criteria in his or her will that will continue to control or affect the distribution of assets long after he or she has died, a concept often referred to as control by the “dead hand” or “mortmain“.

All law students are familiar with the Rule, and Wikipedia describes it as “one of the most difficult topics encountered by law school students.” Although generally an issue with wills, it also may apply to conveyances of “future interests.” The rule was applied in a famous oil and gas case, Peveto v. Starkey, 645 S.W.2d 770 (Tex. 1982). In that case, owners of mineral interests conveyed to Peveto a term royalty interest in their land, for 15 years and so long thereafter as there was production. Thirteen years later, the same owners conveyed to Starkey the same royalty interest they had conveyed to Peveto, but the deed to Starkey provided that “this grant shall become effective only on the expiration of the above described royalty deed to R.L. Peveto.” The Supreme Court held that the conveyance to Starkey violated the Rule Against Perpetuities, because it would not “vest” until some uncertain future date, which could be more than the lifetimes of those then living plus 21 years. Conoco relies on this case to argue that the reservation of a term royalty in its deed violates the Rule. It also argues that the result should be that the royalty is perpetual, not limited as to term, so that Conoco still owns a term royalty in its well even though there was no production from the well in the 15-year term of the royalty reservation.

Conoco’s construction of the Rule Against Perpetuities, in my view, has no application to its royalty reservation. Term royalty conveyances and reservations are common, and no such royalty reservation as ever been held to violate the Rule. The Supreme Court said so much in Peveto v. Starkey. The reversionary interest reserved by the grantor would vest in possession on expiration of the royalty term, but the reversionary interest is “vested in interest” when the deed is delivered, and thus does not violate the rule. As Koopman’s brief says,

If [Conoco’s] argument is adopted, over a century of permitted us of the “as long thereafter” language [in term royalty deeds and reservations] will be in question, opening the door to a flood of litigation and casting uncertainty on the rights of countless mineral estate owners, royalty interest holders, lessees, lessors, and operators.

Perryman v. Spartan, No. 16-0804

Perryman sold land to his son Gary, reserving 1/2 of all royalties from production of oil, gas and other minerals. Gary later conveyed the land to a company they formed called GNP, Inc. The deed to GNP contained the identical reservation language as the deed to Gary, but did not mention the prior reservation of 1/2 of the minerals by his father. GNP borrowed against the property, and the bank subsequently foreclosed and acquired the property by a trustee’s deed; that deed saved and excepted 1/2 of the royalty which is “now owned by Gary Perryman.” The dispute became whether the Duhig rule applies to the deed to GNP. Even though GNP purported to reserve 1/2 of the royalty, since there was a prior reservation of 1/2 of the royalty not mentioned in the GNP deed, the court of appeals held that, under Duhig, the grantor must suffer the burden of the prior reservation, meaning that GNP reserved nothing.

The successors of GNP argue that the Duhig rule should not apply because the deed to GNP conveyed only the interest “now owned by grantor” in the property. They argue that the deed conveyed only whatever interest the grantor owned, so there was no warranty of any interest being conveyed and the reservation is therefore effective.

Smith & Weaver’s Oil and Gas treatise says that Duhig applies to conveyances without warranty but does not apply to “true quitclaim deeds.” A deed conveying “all of Grantor’s interest” has been construed as equivalent to a quitclaim deed — but the deed to GNP did have a general warranty. Perhaps uncertainty as to when the Duhig rule applies will be clarified in this case.

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog