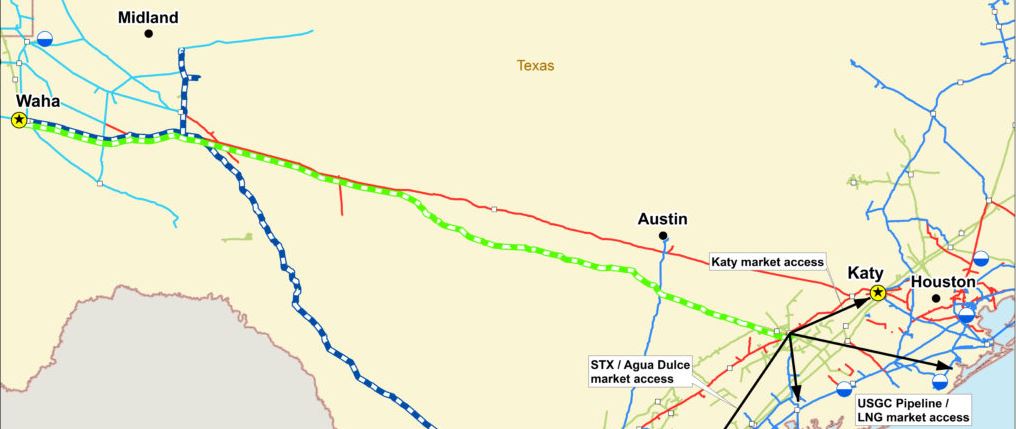

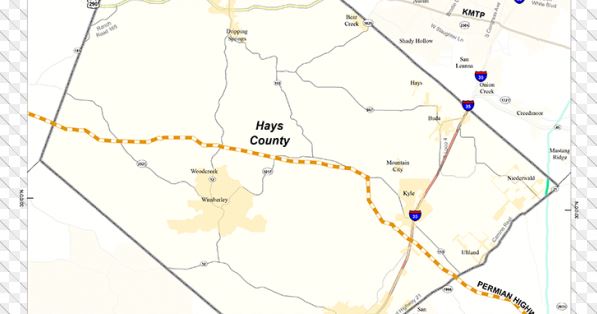

Hays County and the City of Kyle, and private landowners, have sued Kinder Morgan, the Texas Railroad Commission and its commissioners over the route for Kinder Morgan’s Permian Highway Pipeline, a gas pipeline 42 inches in diameter, set to cross through the Texas hill country and Hays County.

The suit claims that the RRC has failed to establish regulations that implement the Legislature’s requirement, imposed by Section 121.052 of the Texas Utilities Code, to “establish fair and equitable rules for the full control and supervision of the pipelines … in all their relations to the public” and to “prescribe and enforce rules for the government and control of pipelines … in respect to transporting … facilities.” The petition explains that, to obtain the right to condemn a pipeline easement, the pipeline company only needs to file a form T-4 with the RRC. The Commission “conducts no investigation, evaluates no alternative routes, entertains no adversarial inquiry, provides no notice, allows no hearing, and considers no evidence.” “The pipeline’s chosen route crosses some of the most sensitive environmental features in Central Texas and the Texas Hill Country, including the recharge zones of the Edwards and Edwards-Trinity Aquifers (which provide the drinking water supply for towns and cities such as Fredericksburg and Blanco) and endangered species habitat.”

The suit claims that the RRC has failed to establish regulations that implement the Legislature’s requirement, imposed by Section 121.052 of the Texas Utilities Code, to “establish fair and equitable rules for the full control and supervision of the pipelines … in all their relations to the public” and to “prescribe and enforce rules for the government and control of pipelines … in respect to transporting … facilities.” The petition explains that, to obtain the right to condemn a pipeline easement, the pipeline company only needs to file a form T-4 with the RRC. The Commission “conducts no investigation, evaluates no alternative routes, entertains no adversarial inquiry, provides no notice, allows no hearing, and considers no evidence.” “The pipeline’s chosen route crosses some of the most sensitive environmental features in Central Texas and the Texas Hill Country, including the recharge zones of the Edwards and Edwards-Trinity Aquifers (which provide the drinking water supply for towns and cities such as Fredericksburg and Blanco) and endangered species habitat.”

The suit asks the court to find that the RRC has unconstitutionally delegated to Kinder Morgan the legislative and constitutional requirement that a government entity review and determine the necessity for the pipeline route, and enjoining Kinder Morgan from proceeding with condemnation until that has been accomplished.

Plaintiffs are represented by Richards Rodriguez & Skeith, LLP and Renea Hicks. The suit is No. D-1-GN-19-002161, in the 345, District Court of Travis County. A copy of the petition can be seen here: 01-OrigPet-Sansom

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog