I ran across a fascinating opinion from the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals that provides a window into Wyoming history. Iron Bar Holdings v. Cape, No. 23-8043, decided March 18.

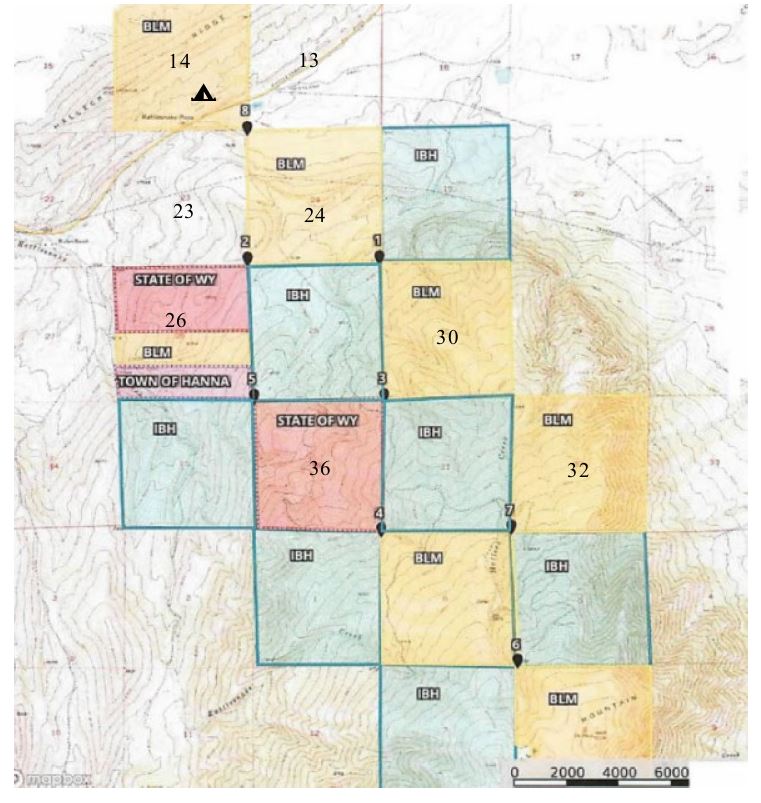

The facts are these: Iron Bar Holdings owns a ranch in southwest Wyoming covering 50 square miles. But within its boundaries are some 11,000 acres of federal and state public lands, some of which are completely enclosed by Iron Bar’s lands. In 2020, three hunters from Missouri decided to travel to Wyoming to hunt elk on public land within Iron Bar’s ranch. They could get to one section wholly surrounded by Iron Bar sections only by crossing over the corner touching two sections of federal land. So they stepped across the corner from Section 14 to Section 24, without setting foot on Section 13 or Section 23.

As stated by the court, “Iron Bar is not friendly to corner-crossers.” It erected no trespassing signs at the corners, and its employees harassed the hunters. But in 2020 they did hunt on Section 24. They returned in 2021 to do the same, but this time Iron Bar convinced the local prosecuting attorney to prosecute the hunters for criminal trespass. They were acquitted in a jury trial. Not satisfied, Iron Bar sued the hunters for civil trespass, seeking $9 million in damages. It is this civil case that eventually ended up in the 10th Circuit.

As stated by the court, “Iron Bar is not friendly to corner-crossers.” It erected no trespassing signs at the corners, and its employees harassed the hunters. But in 2020 they did hunt on Section 24. They returned in 2021 to do the same, but this time Iron Bar convinced the local prosecuting attorney to prosecute the hunters for criminal trespass. They were acquitted in a jury trial. Not satisfied, Iron Bar sued the hunters for civil trespass, seeking $9 million in damages. It is this civil case that eventually ended up in the 10th Circuit.

But how did this whole checkerboard thing come about?

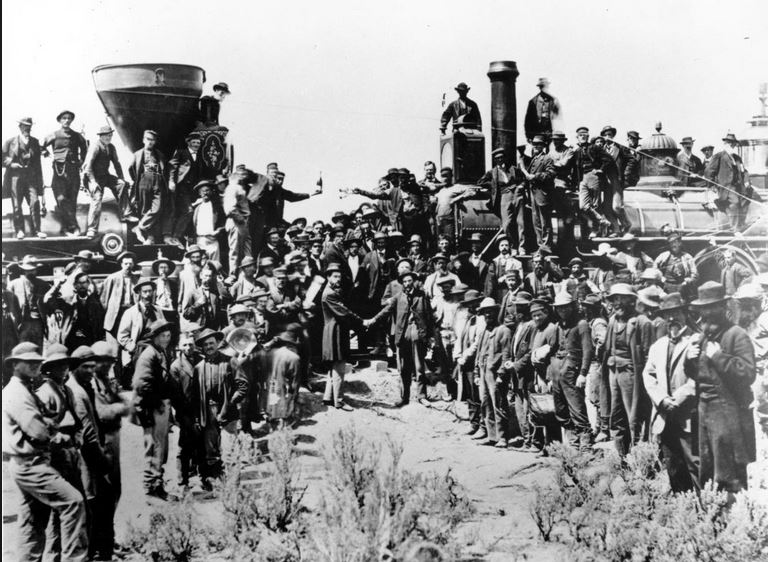

Iron Bar’s ranch is in the southwest corner of Wyoming, which became part of the U.S. as some of the lands ceded to the US in the 1948 Mexican Cession and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Wyoming was admitted as the 44th state in 1890. Prior to that it was the Wyoming Territory. In the 1860s westward expansion, Congress became interested in creating a continental railroad. As a way to compensate the two companies selected to construct the railroad–Union Pacific and Central Pacific—Congress agreed to grant the railroads a section of land for each mile of track laid.

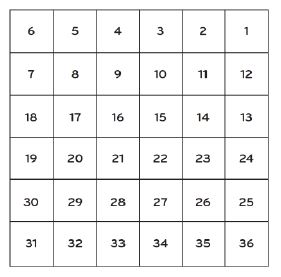

The public land to be granted the railroads was surveyed in townships, each containing 36 sections, along the route of the proposed railroad, in a 20-mile corridor:

The railroads were granted the odd-numbered sections. Congress’ idea was that the railroads’ presence and sale of the granted lands would greatly enhance the value of the retained sections. Construction of the transcontinental railroad began in 1865 and was completed on May 10, 1869.

The checkerboard ownership of railroad surveys soon began to create problems, including the “range wars” between cattlemen and sheep men. (The story told in the series 1923 streaming on Paramount Plus.) Ranch owners built fences that enclosed their lands and the reserved public land sections, keeping sheep herders off the public lands. In response, Congress passed the Unlawful Inclosures Act of 1885. The act was intended to remedy the “matter of great public complaint that cattle companies have unlawfully appropriated and even inclosed by fences great areas of the public domain to the deprivation of the rights of citizens to enter such lands under the laws of the United States, to the obstruction of public travel.” The Unlawful Inclosures Act will come into play in Iron Bar’s trespass case against the hunters.

But, you say, the hunters never set foot on Iron Bar’s property. How could they be trespassing? Here’s where the “ad coelum” doctrine comes into play. It has to do with rights to airspace. Sir Edward Coke established this doctrine as part of the common law of land ownership: ”the earth hath in law a great extend upwards, not only of water as hath been said, but of aire, and all other things even up to heaven, for cujus est solum est usque ad coelum, as it is holden.” This is the idea that a landower’s rights extend down to the center of the earth and upward toward infinity. So if I extend my hand over the fence into your yard, I am trespassing. And if the hunters (as they had to) move over Iron Bar’s land to cross into the public land, that is a trespass under the ad coelum doctrine.

Back to Iron Bar’s trespass case against the hunters. The outcome? The trial court dismissed the case, and the 10th Circuit affirmed. In short, the Unlawful Inclosures Act trumps the ad coelum doctrine.

The 10th Circuit’s opinion contains a thorough review of the cases applying the Unlawful Inclosures Act. In Buford v. Houtz, 133 U.S. 320 (1890), cattlemen sued sheep herders to exclude the sheep from crossing their land to graze their sheep on landlocked public land sections. The court ruled for the sheep herders. In Camfield v. U.S., 167 U.S. 518 (1897) the court held that a rancher could not build a fence so as to exclude the public from public lands within the ranch’s boundaries, citing the Unlawful Inclosures Act. Again in McKelvey v. U.S., 260 U.S. 353 (1922), the court affirmed a conviction of cowboys under the Unlawful Inclosures Act who had prevented sheep herders from crossing their lands to get to public grazing lands. In Leo Sheep Co. v. U.S., 440 U.S. 668 (1979), the court held that the government could not construct a road across private land to provide public access to public lands.

The Unlawful Inclosures Act provides in part:

No person, by force, threats, intimidation, or by any fencing or inclosing .. shall prevent or obstruct … any person from peaceably entering upon or establish a settlement or residence on any trct of public land subject to settlement or entry under the public land laws of the United States, or shall prevent or obstruct free passage or transit over or through the public lands.

The 10th Circuit held that Iron Bar, by its actions, sought to prevent the hunters’ fee passage over or through public lands in violation of the Act.

The controlling principle is that checkerboard landowners cannot maintain a barrier that has the effect of fully enclosing public lands and preventing complete access for a lawful purpose. … when a landowner denies checkerboard access, he imposes a proscribable nuisance under federal law, “notwithstanding such action may involve an entry upon the lands of a private individual.” Camfield, 167 U.S. at 525. At the same time, the government—and by extension its licensees (i.e., the public)—do not have an “implied easement to build a road” across private holdings to reach public lands. Leo Sheep, 440 U.S. at 699.

So the hunters could walk across the corner, but they could not build a road across the corner.

Texas retained its unpatented public land when it joined the Union. Large portions of West Texas at the time were unsurveyed and uninhabited. Texas, like the U.S., granted lands to railroads in exchange for railroad construction, using the same checkerboard pattern. Texas Pacific Railroad obtained hundreds of sections in West Texas by that means. That land is now owned by Texas Pacific Land Corporation, and the minerals under its lands are owned by Chevron. But Texas does not have a statute like the Unlawful Inclosures Act, so Texas Pacific Land Corporation and Chevron arguably have no right of access to landlocked sections they own. The history of Texas Pacific Railroad’s land title is also a great story, which I have written about before.

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog