Christi Craddick, Chairman of the Texas Railroad Commission, testified in Washington yesterday before the House Science and Technology Committee, chaired by Lamar Smith, as part of a panel addressing environmental effects of hydraulic fracturing and wastewater disposal. Introductory remarks and testimony can be viewed here. The testimony reflects, I think, the political polarization in Washington. Because of recent reports about earthquakes in North Texas and Oklahoma, a lot of the testimony related to those issues, as well as the ability of local municipalities to regulate drilling in their jurisdictions – an issue now before the Texas Legislature.

When It Comes to Earthquakes, Oklahoma is Ahead of Texas

Oklahoma regulators have finally awakened to the seismic activity caused by water well injection in their state. Take a look a this new website unveiled this week by the Oklahoma Corporation Commission. And look at their interactive map showing seismic events and injection wells. Oklahoma now surpasses California in seismic activity. Railroad Commission, where are you? Don’t let the Sooners show you up.

SMU Study Links Earthquakes to Oil and Gas Activity in Azle

Beginning in 2013, the town of Azle, in the heart of the Barnett Shale, experienced a “swarm” of earthquakes. Its citizens complained to the Texas Railroad Commission, blaming injection wells for the quakes. When the RRC held a meeting in Azle, refusing to link the quakes to the injection wells, the citizens decided to protest in Austin. They bussed themselves to a RRC open meeting, where they serenaded the commissioners with a song from Elvis, “All Shook Up.”

Southern Methodist University scientists have now published a paper concluding that the Azle quakes were “most likely” caused by the injection wells, together with withdrawals of produced water by the seventy-plus producing wells in the area. SMU installed monitors around Azle after the quakes began,and identified a fault running through the area. The scientists developed a model showing that the changes in pressure caused by the withdrawals on one side of the fault and the injections on the other were the likely cause of the quakes. Heather DeShon, one of the SMU researchers, said that “What we refer to as induced seismicity – earthquakes caused by something other than strictly natural forces – is often associated with subsurface pressure changes. We can rule out stress changes induced by local water table changes. While some uncertainties remain, it is unlikely that natural increases to tectonic stresses led to these events.”

The Texas Railroad Commission website stills says that “Texas has a long history of safe injection, and staff has not identified a significant correlation between faulting and injection practices.” After Azle’s visit to the RRC, it hired its own seismologist, David Pearson. In response to the SMU report, Pearson said that “We will not be suspending activity at the two wells, especially given the fact that we have not seen any continuation of large-scale earthquakes in the Azle area that would give us any cause for alarm. The swarm has died out and has been quiet for some time.” Milton Rister, the Railroad Commission’s executive director, wrote a letter requesting a meeting with the SMU researchers.

1,500 Uncompleted Wells in Eagle Ford Shale?

FuelFix reports that companies have drilled but not completed wells, in effect storing the reserves in the ground until oil prices rise and completion costs decline. FuelFix says that IHS Energy counts 3,000 uncompleted wells in the US, including 1,500 uncompleted wells in the Eagle Ford alone. It says that Apache, Anadarko and Cabot have 845 uncompleted wells in Texas, with a potential to produce 373,000 barrels of oil and 528 million cubic feet of gas a day.

Will Cities Lose their Power to Regulate Urban Drilling?

Last month I wrote about the Texas legislature’s efforts to limit cities’ authority to regulate drilling within their jurisdictions, after the City of Denton passed a ban on hydraulic fracturing. The bill that has emerged is House Bill 40, sponsored by Drew Darby, chairman of the House Energy Resources Committee. It passed out of committee, but yesterday was returned to committee on a technicality. A companion bill in the Senate, Senate Bill 1165, has also passed out of its Natural Resources committee.

The bill would greatly limit cities’ ability to regulate drilling. It provides that cities may only regulate “aboveground activity related to an oil and gas operation that occurs at or above the surface of the ground, including a regulation governing fire and emergency response, traffic, lights, or noise, or imposing notice or reasonable setback requirements.” Any ordinance must be “commercially reasonable,” defined as “a condition that would allow a reasonably prudent operator to produce, process and transport oil and gas, as determined based on the objective standard of a reasonably prudent operator and not on an individualized assessment of an actual operator’s capacity to act.”

The bill leaves may questions unanswered. For example, Fort Worth has an ordinance that regulates saltwater pipelines. Are pipelines an “aboveground activity” that cities can regulate?

House Bill 1552 and Allocation Wells

Yesterday the Energy Resources Committee of the Texas House of Representatives heard testimony on HB 1552, introduced by one of its members, Rep. Tom Craddick. The bill deals with “allocation wells,” of which I have written before. An allocation well is a horizontal well that crosses over two or more tracts without combining those tracts into a pooled unit or obtaining agreement from the royalty owners in the tracts on how production from the well will be allocated among the tracts.

Although the Texas Railroad Commission issues permits for allocation wells, there has been a lot of speculation about whether leases grant the authority to drill such wells. At the hearing, representatives of operators spoke in favor of the bill, and mineral owners spoke in opposition. I spoke in opposition on behalf of Texas Land and Mineral Owners Association.

A substitute for the original filed bill was introduced at the hearing. HB 1552 substitute

“The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.”

Everyone knows this quote and that it is from Shakespeare. It is from Henry VI, Part 2. And it has generated some controversy.

Defenders of lawyers (mostly lawyers) say that it is misunderstood and was intended as a “complement to lawyers and judges who protect the people from tyranny and anarchy.” This argument stems from the identity of the character speaking, Dick the Butcher, a dastardly villain and follower of the rebel Jack Cade, a pretender to the throne and a sort of libertarian. Dick the Butcher was supporting Jack Cade’s campaign and encouraging him in his quest for anarchy.

But not so fast, say others. In fact, Dick the Butcher is making a joke, as Shakespeare was wont to do, at the expense of lawyers.

Second Annual GDHM Seminar May 8

Our firm will host a seminar in Austin for land and mineral owners on May 8. Open to the public, but you have to register. You can register here.

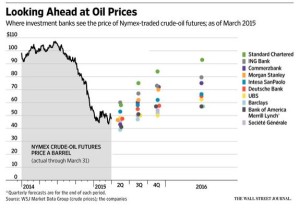

Major Banks’ Oil Price Predictions

Cities vs. Industry: Fight over Municipal Regulation of Fracking Continues at Legislature

Struggles over fracking bans have been in the news for some time in Pennsylvania, Colorado, Ohio, New Mexico and other states. The State of New York has had a moratorium on fracking for several years. But until recently, cities and oil and gas companies in Texas had been able to get along. Until, that is, the City of Denton, Texas passed a referendum banning fracking with in its city limits. Since then, as we say in Texas, all hell has broken loose.

The day after Denton’s referendum passed, two suits were filed challenging its ordinance, one by the Texas General Land Office and one by the Texas Oil and Gas Association. In the Legislature, several bills were filed to limit municipal authority to regulate drilling. One bill would require cities to reimburse the state for lost revenue from any drilling ban. Another would require cities to get approval from the Attorney General before putting any referendum on the ballot.

The two bills that appear to have the most legs are HB 2855, introduced by Drew Darby, and SB 1165, introduced by Troy Fraser. SB 1165 has been favorably reported out of the Senate Natural Resources Committee. HB 2855 remains pending in the House Energy Resources Committee after a lengthy hearing at which representatives of the industry and municipalities testified late into the night.