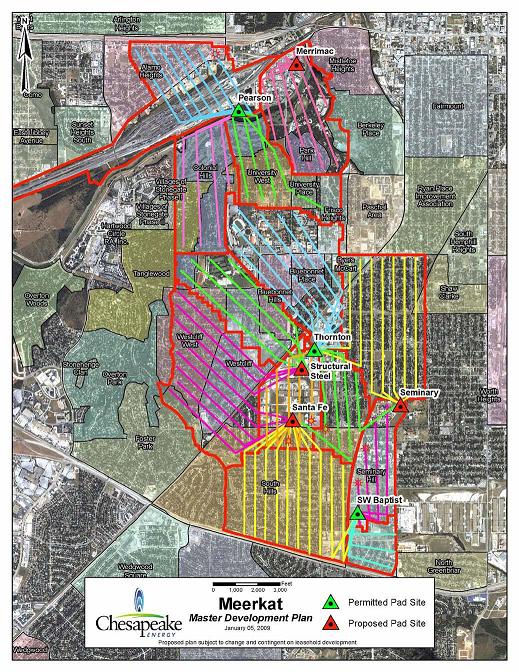

Chesapeake Energy has obtained City approval for a “master drilling plan” that lays out plans to drill 69 horizontal wells from seven drilling locations within the City of Fort Worth. The plan identifies the drilling locations and the gathering lines, and how produced water will be disposed of. The plan shows how horizontal drilling technology has revolutionized the drilling of wells in shale formations.

Texas Supreme Court Record on Royalty Owner Cases

In a previous post I discussed a recent Texas Supreme Court case, Exxon v. Emerald, reversing a multimillion-dollar judgment against Exxon for intentionally sabatoging wells so that they could not be re-entered. This nudged me to look at other royalty-owner related cases handed down by the Texas Supreme Court over the last ten years. The court’s record is not a good one for royalty owners. Highlights of the Court’s work:

HECI v. Neel (1998). HECI sued an adjacent operator for illegal production on an adjoining lease that damaged the common reservoir underlying both leases, and recovered a judgment for more than $3.7 million. HECI did not inform its royalty owners of the suit and did not share any of the judgment proceeds with the royalty owners. When HECI’s royalty owners found out about the suit, they sued HECI to recover their share of the judgment. The Supreme Court held that the royalty owners had waited too long to bring their suit, even though they did not find out about the suit until five years after the trial. The Court held that the royalty owners should have known that the adjacent operator was damaging the common reservoir by its operations.

Yzaguirre v. KCS Resources (2001). Plaintiffs were royalty owners who received royalties under a lease operated by KCS. KCS sold its gas under a 20-year contract with Tennessee Gas Pipeline, and the price under the Tennessee contract greatly exceeded the spot market price of the gas. But KCS paid royalties based on the “market value” of the gas, using comparable spot sale prices, well below the price it received from Tennessee. The Court held that KCS did not owe royalties based on the Tennessee price — and, it held that the Tennessee contract was not even competent evidence of the market value of the gas.

Wind Energy in Texas

Renewable energy is a hot topic in the new Obama Administration. Wind Energy is being touted, especially in Texas, as a solution to global warming and U.S. dependence on foreign oil. Wind farms have sprouted all across Texas. Texas is now the leading wind energy producing state. Texas utilities are about to spend billions of dollars extending high-voltage transmission lines into West Texas and the Panhandle, opening up those areas to additional wind energy projects. The Texas Panhandle will see the next boom in wind energy development. Having grown up in the Panhandle, I can verify that the wind blows there.

Three points are good to keep in mind when reading stories about renewable energy in general, and wind energy in particular. First, it is important to distinguish between two different goals being pursued by the Obama Administration: freedom from dependence on foreign oil, and reduction of carbon emissions. Wind energy is “clean,” because it does not produce CO2. To the extent that wind energy can replace conventional coal- and natural gas-burning power plants, it therefore reduces CO2 emissions, thus fighting global warming. But wind energy has little or no effect on imports of oil, which is mostly used for fueling cars and trucks. If and when the auto industry solves the battery problem and is able to produce electric cars, wind energy could contribute to reduction in oil imports.

Second, it is important to understand that, although wind farms are increasing exponentially, they contribute only a tiny portion of the nation’s total energy consumption. According to the Energy Information Administration, as illustrated below, in 2007 wind energy contributed only 5% of 7% of the nation’s energy — .35%!

Exxon v. Emerald

On March 27, the Texas Supreme Court issued its opinions in two related cases, both styled Exxon Corporation v. Emerald Oil & Gas Company. The cases were argued before the court more than two years ago, and the decisions were awaited with much anticipation. The Court reversed a judgment against Exxon for $8.6 million in actual damages and $10 million in punitive damages.

The facts in the case are remarkable. In the 1950’s Exxon’s predecessor Humble Oil & Refining Company obtained oil and gas leases covering several thousand acres in Refugio County owned by the O’Connor family. The leases were quite unusual; among other things, they provided for a 50% landowners’ royalty. Exxon drilled 121 wells and produced more than 15 million barrels of oil and 65 billion cubic feet of gas from the O’Connor lands. In the 1980’s Exxon asked the O’Connors to reduced their royalty, claiming that the leases were becoming uneconomical. Those negotiations failed, and in 1989 Exxon notified the O’Connors that it intended to start plugging wells and abandoning the leases. Negotiations for the O’Connors to take over operation of the wells were not successful, and Exxon began plugging wells and abandoning the leases.

Use of Bank Drafts for Bonus Payment in Oil and Gas Leasing

Exploration companies have traditionally used bank drafts to pay bonuses for oil and gas leases. Since drafts look a lot like a check, they can be misleading to mineral owners. Some mineral owners’ recent experiences with dishonored drafts have highlighted the problems with use of these financial instruments.

A draft is like a check, but different. It is an order issued to a bank to pay a party, conditioned on the happening of a specified event. As used by exploration companies, it is an order issued by a company or its landman to the company’s bank to pay the bonus to the mineral owner. Typically, the draft provides that the company has a period of time – 30 to 90 days – from the date its bank receives the draft to “honor” the draft – that is, to tell the bank to pay the bonus to the mineral owner. The draft typically has language like the following:

On approval of lease or mineral deed described herein, and on approval of title to same by drawee not later than 30 days after arrival of this draft at collecting bank.

In other words, the company has 30 days to approve the oil and gas lease being paid for and to approve the mineral owner’s title to the minerals being leased. If the company does not approve the lease, or if it determines that the mineral owner does not have good title to the minerals being leased, it can refuse to pay the draft.

Use of drafts to pay for leases would seem to be a good way, in theory, to facilitate the lease transaction. And in fact, drafts are used every day in hundreds of lease transactions, without incident. But there are problems with its use, and those problems can put landowners at risk. My advice to landowners is to avoid using drafts if possible.

Oil and Gas Lease Termination Clauses

Last week I discussed Wagner & Brown v. Sheppard, a recent Texas Supreme Court case that involved a lease termination clause. Sheppard’s lease in that case provided that, if royalties were not paid to her within 120 days after first production, the lease would automatically terminate. That is exactly what happened.

Landowners are usually surpriesed to learn that, under a “standard form” oil and gas lease, the lessee’s failure to pay royalties does not give the lessor the right to terminate the lease. The lease remains in effect, and the lessor’s only remedy is to sue for the unpaid royalties. Landowners often seek to negotiate a clause like Sheppard’s that gives the lessor the right to terminate the lease for failure to pay royalties. Exploration companies of course do not like such a provision. It puts them at risk that, if royalties are not timely paid for some inadvertent reason, they can lose the lease even though they are willing and able to pay the royalties.

First, I think it is not a good idea to include a provision that a lease terminates automatically if royalties are not paid within a specified time. Depending on the circumstances, it may not be in the lessor’s best interest to terminate the lease, even though royalties have been delayed. A better provision is that, if royalties are not paid by a specified date, the lessor has the option to terminate the lease.

What happens to a pooled lease when the lease terminates?

A recent decision of the Texas Supreme Court, Wagner & Brown, Ltd. v. Sheppard, has caused quite a stir in oil and gas legal circles. The court was faced with a question never before answered by a Texas appellate court, what is known as a “case of first impression.” Such cases are always interesting to oil and gas lawyers, so I thought I would weigh in on the arguments.

The facts in the case are these: Jane Sheppard owns a 1/8th mineral interest in 62.72 acres in Upshur County. She leased her 1/8th interest, and her lease – along with leases of the other 7/8ths interest in the 62.72 acres and leases of other lands- was pooled to form the W.M. Landers Gas Unit, containing 122.16 acres. Two wells were drilled on Sheppard’s tract, both producing gas.

Sheppard’s lease contains a provision requiring payment of royalties within 120 days of first sales of gas, failing which the lease would terminate. She was not paid on time, and her lease terminated.

Texas law is clear that, if there had been no pooled unit, upon termination of her lease Sheppard would become what is known as a “non-consenting co-tenant” in the two wells on her tract. She would be entitled to receive her 1/8th share of proceeds of sale of gas from the wells, less 1/8th of the costs of production and marketing. But Wagner & Brown contended that Sheppard’s tract was still bound by the pooled unit, even though her lease had expired. Under the pooling clause in Sheppard’s lease, her royalty would be calculated based on the number of acres of her tract compared to the total number of acres in the unit – in this case, 62.72/122.16, or 51.34% of the wells’ production. Wagner & Brown contended that Sheppard should receive 1/8th of 51.34% of production from the wells, less that same fraction of the cost of production and marketing. The Supreme Court agreed with Wagner & Brown, holding that “the termination of Sheppard’s lease did not terminate her participation in the unit.”

Surface Damages for Oil and Gas Activities in Texas

Landowners in Texas are often surprised to learn that oil companies have no obligation to compensate them for use of their lands, or to restore the lands after their use, absent a contractual requirement to do so in their oil and gas lease. The typical oil-company form lease provides only that the lessee will pay for damages “caused by its operations to growing crops and timber on the land.” Under such a lease, the company does not have to compensate the surface owner for use of or damage to the surface caused by its operations.

Most exploration companies do compensate the surface owner for surface use. The usual practice is for the company to agree with the surface owner on a single lump-sum payment for each well location, with its attendant roads and flow line easements. The company pays this compensation for two reasons: first, to maintain good relations with the surface owner, and second, to obtain from the surface owner a release, which is presented to the surface owner at the time of the payment. The release typically contains language absolving the company from any and all damages caused by the company’s operations on the property for the well. In other words, part of the consideration for the payment is the landowner’s release of the company from further liability.

Absent a contractual obligation in the lease, the oil company has no obligation to compensate the landowner unless it negligently or intentionally causes damages in excess of the reasonable and necessary damages resulting from its operations. The mineral estate is the “dominant estate,” which means that the mineral owner and his/her lessee have the right to use so much of the surface estate as is reasonably necessary to explore for and produce oil and gas. Texas courts have historically been very careful to protect the rights of the mineral lessee. After all, the oil and gas industry was the principal source of wealth and revenue in Texas for decades, and courts obligingly crafted legal principles designed to facilitate oil and gas exploration and production.

Ruminations on Unconventional Resource Plays

The last few years have seen a boom in the oil and gas exploration business in the U.S., driven by new technologies that have allowed exploitation of “unconventional” resources for gas and oil. These resources are often called “resource” plays, because the oil and gas is being produced from shale beds. Shale is known by geologists to be the source or “resource” of pockets of oil and gas accumulated over hundreds of years in more conventional oil and gas sands, trapped by faults and other geological anomalies.

The resource plays in the news over the last couple of years are the Barnett Shale in Texas, in and around Fort Worth, the Fayetteville Shale in Arkansas, the Bakken Shale in North Dakota, and more recently the Marcellus Shale in Pennsylvania and New York, the Haynesville Shale in Louisiana and East Texas, and the recently discovered Eagle Ford Shale in South Texas. Exploitation of these resources has resulted from two factors: improved technology, especially horizontal drilling, and high oil and gas prices. The discovery and exploitation of these shale plays has dramatically increased the U.S. reserves of natural gas. The top producing well in the Haynesville Shale produced 713 million cubic feet of gas in December, an average of 23 mmcf per day.

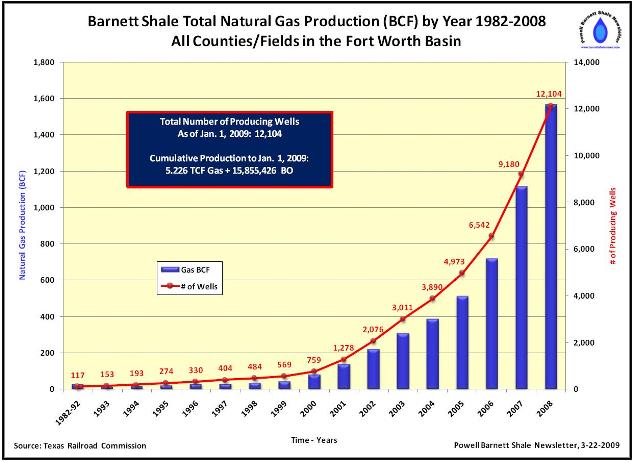

The table below shows the increase in production from the Barnett Shale since 1982:

These shale plays have had dramatic effects in the U.S. economy and in U.S., state and local politics. For example:

— Lease bonuses in the Barnett and Haynesville Shale plays reached heights unheard of last year — $25,000 to $30,000 per acre. By September 2008, Chesapeake had acquired leases covering 550,000 acres, EnCana and Shell had bought 325,000 acres, Petrohawk Energy 275,000 acres, Devon energy 130,000 acres. Haynesville lease bonuses averaged more than $13,400/acre. The Haynesville play was like the California gold rush.

— The Haynesville Shale is 200-300 feet thick. Recoverable gas reserves are estimated at 24-60 Bcf (billion cubic fee, or a million mcf) per square mile. Estimated ultimate recoveries from Haynesville wells have been estimated at 4.5 to 8.5 Bcf per well.

— In and around Fort Worth, and in areas of Pennsylvania, landowners began to organize themselves to bargain with exploration companies as a group, to increase their leverage to obtain better lease terms.

— Ray Perryman, a Texas economist, estimated that the economic impact of the Barnett Shale on the Barnett Shale Region in 2008 was almost $30 Billion.

— Horizontal drilling technology has allowed the drilling of wells in urban areas, including under the DFW Airport and under the campus of Texas Christian University in Fort Worth.

— Urban drilling has also lead to increased regulation by municipalities of drilling activities in urban areas. Fort Worth and surrounding cities have adopted increasingly sophisticated and complex drilling ordinances, regulating aspects of drilling and producing wells that have not heretofore been the subject of regulation, including sound abatement, air pollution, pipeline safety, and street maintenance.

— Members of the Texas Legislature, now in session, have introduced numerous bills – principally in response to complaints by constituents – to allow municipalities, counties and groundwater districts some authority to regulate condemnation for and location of pipelines, underground disposal of produced water and frac water, and “the quality of the environment.” Industry lobbyists are being kept busy opposing those bills.

— The Pennsylvania Legislature is considering bills to impose a property tax on producing minerals and a severance tax on production in that state.

Post-Production Costs in Texas-Part III: Yturria v. Kerr-McGee

Last week, in Post-Production Costs in Texas-Part II, I discussed the Texas Supreme Court’s decision in Heritage Resources v. NationsBank regarding the deductibility of post-production costs from lessor’s royalties under an oil and gas lease. Justice Priscilla Owen (now a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit) filed a concurring opinion in Heritage in which she said that “it is important to note that we are construing specific language in specific oil and gas leases. Parties to a lease may allocate costs, including post-production or marketing costs, as they choose.” Justice Owen’s conclusion was put to the test in Yturria v. Kerr-McGee Oil & Gas Onshore, LLC, decided by the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals on September 8, 2008.

My firm represented the royalty owners in Yturria v. Kerr McGee, and I was the author of two of the oil and gas leases construed in that case. As the court points out, these were not “standard” oil and gas leases. They contained detailed provisions as to how royalties were to be calculated and paid. The language was crafted as part of the settlement of earlier litigation with Kerr McGee over royalty payments, and at the time the language was agreed to there were existing wells on the leases that produced substantial quantities of gas. The Kerr-McGee gas was processed before sale under a processing agreement between Kerr-McGee and the processor, Enterprise.; The processing agreement required that Enterprise pay Kerr McGee for 80% of the natural gas liquids extracted from the gas, based on posted prices, less a “T & F Fee” for the costs of transportation and fractionation of the liquids. The issue in the case was whether the royalty owners should bear their royalty share of the T & F Fees charged by Enterprise. The trial court and the court of appeals both ruled in favor of the royalty owners, holding that, under the particular language of the leases, the T & Fees could not be deducted from the lessors’ royalty.

The leases provided that Kerr-McGee would pay a royalty on natural gas liquids (called “plant products” in the leases) equal to “1/4th of 75% of all plant products, or revenue derived therefrom, attributable to gas produced by Lessee from the leased premises (whether or not Lessee’s processing agreement entitles it to a greater or lesser percentage).” The leases also provided that “Lessor’s royalty shall never bear, either directly or indirectly, any part of the costs or expenses of production, gathering, dehydration, compression, transportation (except transportation by truck), manufacture, processing, treatment or marketing of the oil or gas from the leased premises.” The court of appeals agreed with the royalty owners that the “revenue derived” from plant products was the gross revenue based on the price set forth in the Enterprise-Kerr-McGee processing agreement, before deduction of the T & F Fees.