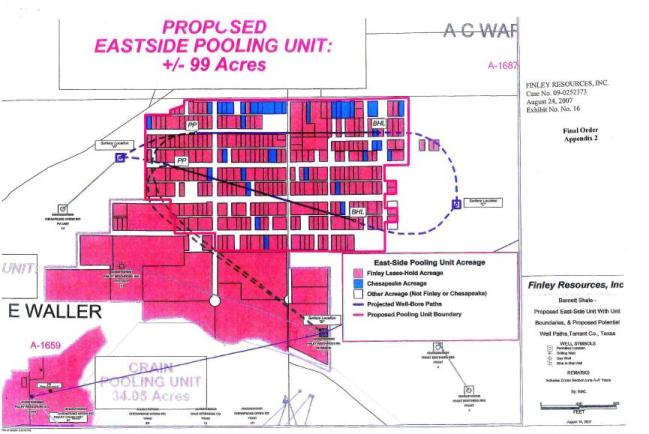

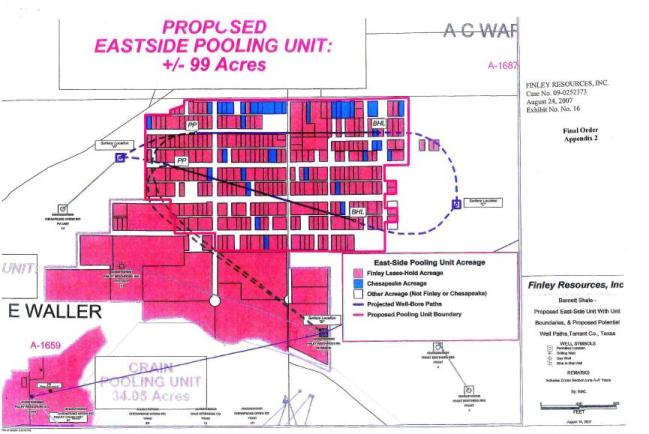

The Texas Railroad Commission handed down an interesting order last August that may have broad application for operators’ use of Texas’ Mineral Interest Pooling Act to force unleased mineral owners into pooled units. In Docket No. 09-0252375, Finley Resources applied under the MIPA to form a pooled unit in the Barnett Shale consisting of 96.32 acres, for the drilling of a horizontal well. The proposed unit is in an urbanized area with numerous lots, and Finley was evidently unable to get all lot owners to sign leases. A plat of the proposed unit is shown below. As can be seen from the plat, there are a lot of unleased lots (the white spaces) in the proposed unit.

Under the MIPA, the operator seeking to form the unit must make a “good faith offer” to unleased owners before filing an MIPA application to force them into the unit. Finley offered the unleased lot owners the right to receive a 1/5th royalty and a 4/5ths working interest, which means that 45ths of those owners’ share of production from the well would bear its share of the drilling and operating costs of the well. After studying the matter for a year, the Railroad Commission approved Finley’s application. One unusual aspect of the order is that the unleased owners suffer no “risk penalty.” In most MIPA applications, a party who has refused to join the unit voluntarily must bear its share of the drilling costs plus a “risk penalty,” not to exceed 100% of the drilling and completion costs, before participating in revenues from the well. The Commission’s order in Finley allows the unleased owners to participate in revenues as a working interest owner once the operator has recovered 100% of drilling and completion costs, with no “risk penalty.”

Continue reading →