In this case, decided last April, the Texas Supreme Court held that the force majeure clause in an oil and gas lease could not be relied on to extend the date by which a well had to be commenced to keep the lease in force.

The facts are these:

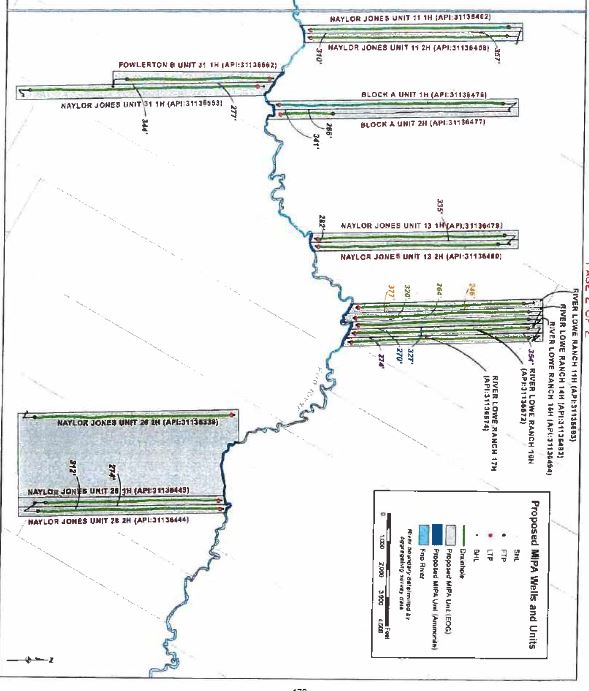

MRC owned a lease covering 4,000 acres in Loving County. The lease provided that, at the end of the primary term, the lease would terminate except as to designated production units around existing wells unless MRC engaged in “continuous drilling”—spudding a well within 180 days after the spud date of the previous well. Prior to the end of the primary term MRC had drilled five wells on the lease. Under continuous drilling clause, MRC had to spud a well by May 21, 2016 to avoid partial termination of the lease.

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog