Over the last 100 years courts have developed a body of case law in disputes between lessors and lessees of oil and gas leases. Courts have held that certain provisions are “implied” in the contracts, even though there is no language in the lease to support those provisions. The rationale behind these implied provisions goes back to cases interpreting hard mineral leases, and back to the cradle of the oil industry, Pennsylvania. The idea behind these implied provisions is that they are necessary for both parties to get the benefit of their bargain and to make the lease work as intended. Because the lessee has control over what operations are conducted under the lease, most of these implied provisions are intended to benefit the lessor, who generally has less bargaining power in negotiation of the lease and no say in whether and how the lease is developed.

An example: oil and gas leases generally provide that the lease will remain in effect for the primary term and for as long thereafter as oil or gas is produced from the leased premises. Courts have implied a requirement that, for the lease to remain in effect, the production must be in “paying quantities.” The production must be sufficient for the lessee to realize a profit over operating costs.

Another example: what if the well on the lease temporarily ceases production at some point after the end of the primary term. Does the lease terminate, even if the well can be repaired and restored to production? Courts developed the implied provision that a “temporary” cessation of production will not cause the lease to terminate, as long as the lessee acts with reasonable diligence to restore production.

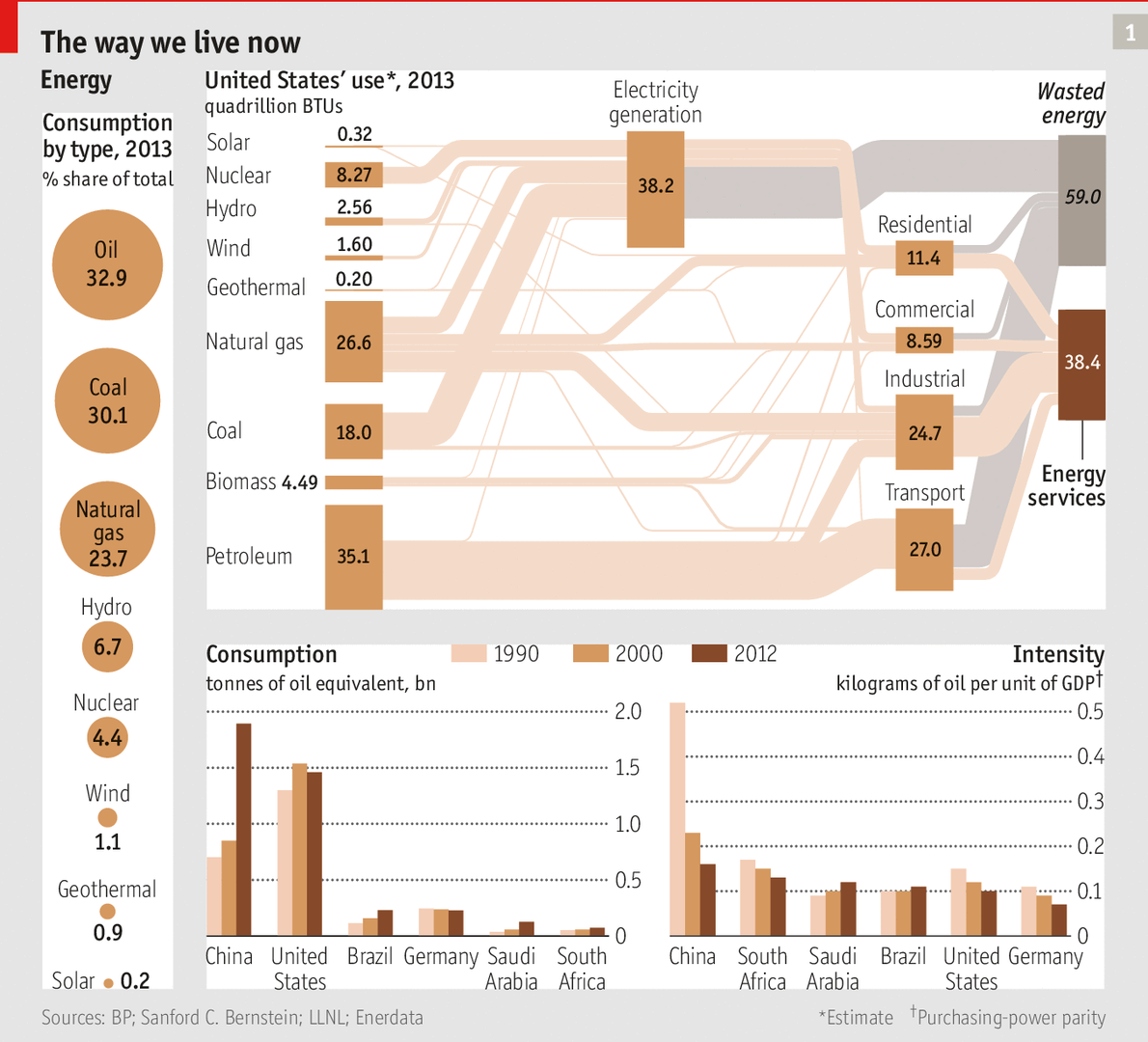

This picture doesn’t present a very optimistic view. Almost 60% of energy production is “wasted energy.” Oil still provides 33% of all energy consumed, while wind supplies only 1.1%, and solar only 0.2%. And the EIA projects that global demand for energy will increase by 37% in the next 25 years.

This picture doesn’t present a very optimistic view. Almost 60% of energy production is “wasted energy.” Oil still provides 33% of all energy consumed, while wind supplies only 1.1%, and solar only 0.2%. And the EIA projects that global demand for energy will increase by 37% in the next 25 years.