The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals has held that a landowner has stated a judiciable claim against the Brazos Valley Groundwater Conservation District (BVGCD) for an unconstitutional taking of his groundwater rights. David Strata, et al. v. Jan A. Roe, et al., No. 18-60994. Fascinating facts.

Groundwater Districts were created by the Texas Legislature to manage production of groundwater. Most Districts cover one county. The BVGCD covers Robertson and Brazos Counties. There are nearly 100 Districts encompassing 72 percent of major and minor aquifers in the State. Each District adopts its own rules governing permitting of and production from water wells.

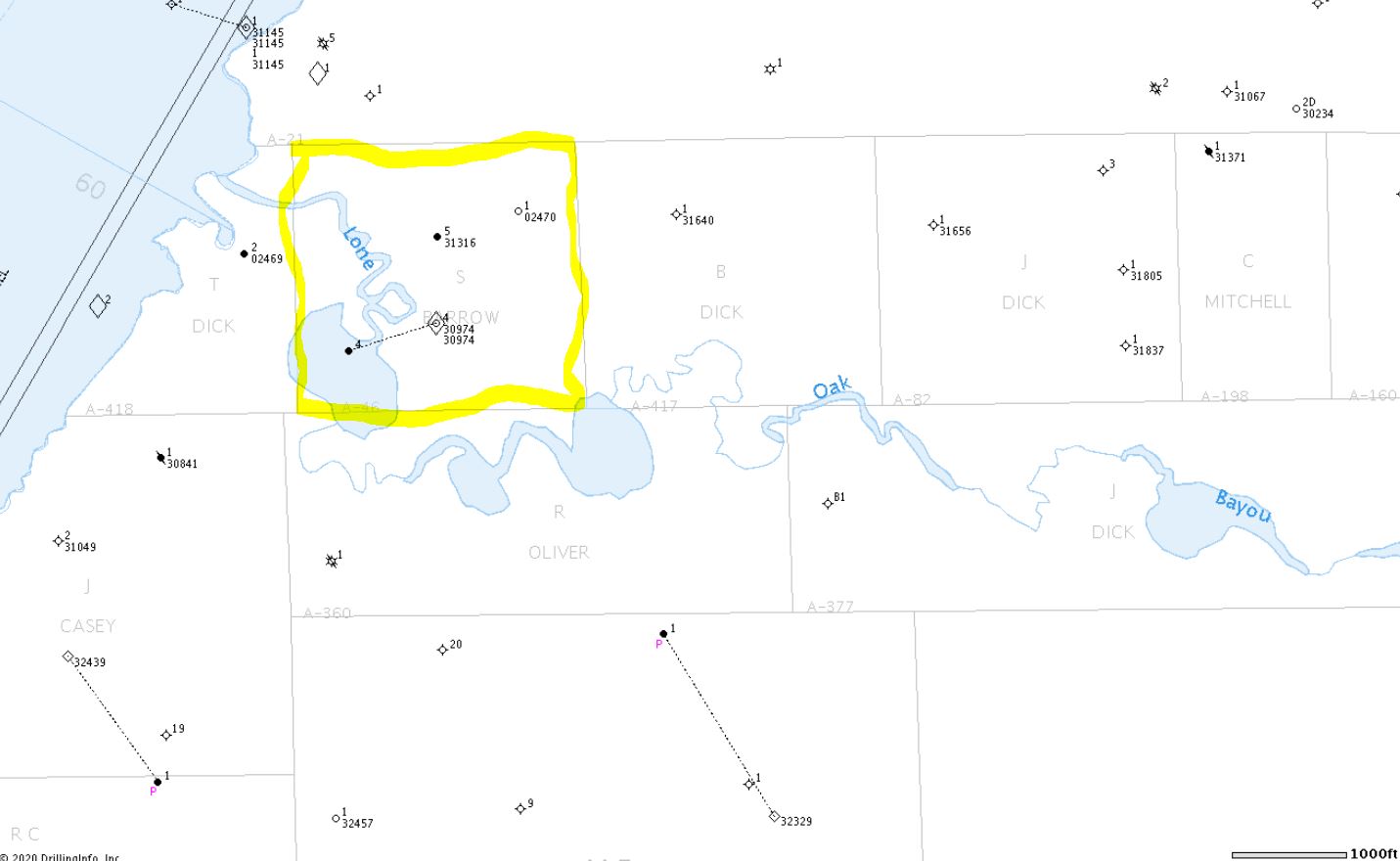

BVGCD’s rules create three categories of water wells: Existing Wells, New Wells, and Wells with Historic Use. Its rules are designed to “minimize as far as practicable the drawdown of the water table and the reduction of artesian pressure, to control subsidence, to prevent interference between wells, to prevent degradation of water quality, and to prevent waste.” The rules provide that Historic Use Wells are generally limited to producing the maximum amount of groundwater used before the effective date of the District’s rules. New Wells have a maximum allowable production based on the number of contiguous acres assigned to the well. When a water well is produced it creates a “cone of depression” in the aquifer – the more water withdrawn, the greater the cone of depression. The District’s rules establish a formula that calculates the amount of water that can be withdrawn from a well based on the number of acres assigned to the well. For example, a New Well producing 3,00 gallons per minute must have 649 continuous acres assigned the well – a circle with a radius of 3,003 feet. No other wells may be permitted in this 649 acres. The District’s rules define “Existing Wells” as those wells “for which drilling or significant development of the well commenced before the effective date of these Rules.” But the rules do not establish production limits for Existing Wells that have no established historic use. Continue reading →

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog

Oil and Gas Lawyer Blog